Birdwatching With British Nature Writer Simon Barnes

Birdwatching with British nature writer Simon Barnes reminds one of what President Kennedy said of Churchill quoting Edward Murrow, “He mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.”

By contrast, Barnes mobilizes the English language and sends it happily birdwatching in his book The Meaning of Birds. Into the field to look for wood pigeons.

It is so British.

Birdwatching, BRITISHLY

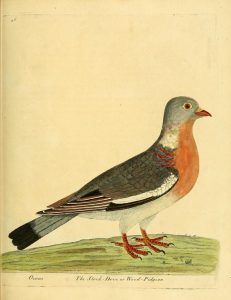

In Barnes’ opinion, the wood pigeon is one of the most beautiful of British birds. But it is common and therefore under-appreciated. To Barnes, however, it is poetry. He describes it thus, “The sides of the neck are glossy purple and green….” “The pale yellow eyes add drama to the head.” And, “the front is a rich pinky-purple merging subtly into rich textures of mushroom and mauve.”

Nature WRITER 101: FiRST FIND SOME ANIMALS

The seemingly quaint hobby of birdwatching is a world-wide industry. Its economic impact in the United States is yuge. Why are we such open-walleted fools for birds?

Barnes explains. “We’re mammals you and I, so why don’t we go out mammal-watching? Because we wouldn’t see any that’s why….” Duh.

We landlubbers harbor a great love for our sky-master feathered friends because we can readily see them. Birds, like humans, are animals for whom sight is the primary sense.

Sure, you can be a mammal watcher, says Barnes. But, “If you want to be a mammal watcher, you must resign yourself to being a turd-watcher.” Ha. He continues, “You don’t often see mammals themselves; the best you can do is to record the signs they leave behind them….It’s always good to find an otter turd, but it doesn’t touch my heart.”

Their Tranquil Cooing

However, birds, unlike turds, are heart- and soul-touching.

Barnes calls the kingfisher “the bird of dreams.” He talks about doves being religious birds long before Christianity. “How could they not be?…Their tranquil cooing told us that all is well.”

Where else but in a philosophically-minded British birdwatching book would you have a reference to The Epic of Gilgamesh and this sentence, “If time travel were possible, I’d take my Tardis to New Zealand a few years before 1280.”

Why there and then? Because feh, mammals.

Barnes writes that in prehistoric New Zealand, “Here evolution took the most extraordinary direction, because on this comparatively enormous landmass there were no mammals at all…Here was a vast area of land with birds as the dominant large life forms.” In fact, the kiwi bird, “has so effectively adopted the mammalian lifestyle that it looks more like a mammal than a bird.” Barnes is nostalgic. He longs for glimpse of long ago Bird Land.

“All gone. And with them a world.” Thankfully we still have the wood pigeon. Because when we arrived by canoe, most of New Zealand’s bounty of ground-dwelling birds became extinct.