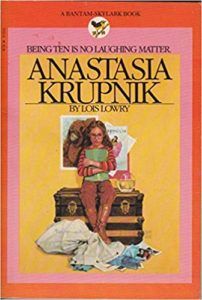

Why Anastasia Krupnik Was Way Ahead of Her Time

In the late ‘90s, I discovered Lois Lowry’s middle grade Anastasia Krupnik books in my elementary school library and immediately had to read the whole series. I related deeply to Anastasia, a bookish, inquisitive, and dramatic girl. She, her little brother Sam, and her quirky parents were by far the most similar characters to my family that I’d ever found. Madeleine L’Engle’s loving families talk to each other in a way that I found oddly formal. In contrast, Anastasia’s parents support her unconditionally while bantering casually.

As an adult, I understand why these books are frequently challenged and banned. They introduce adult topics like death, sex, and alcohol in a way that some people would find irreverent or inappropriate. Published between the late 1970s and 1990s, the books contain cultural and technological references that sound dated today. Overall, though, I think that the series holds up well. Here are a few reasons why the Anastasia books still seem so modern, even today:

She chronicles her thoughts obsessively. In the first book, each chapter ends with a list of Anastasia’s loves and hates. The rest of the series contains similar lists, which Anastasia crosses out and updates, according to her mood. People have always used diaries to chronicle their lives privately. However, the idea of recording fleeting likes and dislikes was new to me in the ‘90s. With social media profiles and playlists, the compulsion to keep track of our favorites seems more common today.

She catfishes a guy. Long before dating apps, Anastasia utilizes the 1991 equivalent of online dating: newspaper personals ads. In Anastasia at This Address, she replies to an ad from a 28-year-old “SWM” (single white male) with a photo of her mother when she was in her twenties. Anastasia rationalizes that this is what she’ll look like at that age. Nowadays, we understand the dangers that children can face from adults online. Luckily, it ends hilariously but is also a cautionary tale about misrepresenting yourself.

She’s not afraid to take risks or leave her comfort zone. In Anastasia’s Chosen Career, she signs up for a modeling class after getting a class assignment about her career plans. She’s never had any interest in modeling but is sold on the class’s promise of developing self-confidence and “poise.” For an academically talented student like Anastasia, it’s a learning experience to realize that she won’t be the star of every class.

Her parents don’t tolerance prejudice—even ironically. In Anastasia at Your Service, she has a summer job working for an elderly, rich woman. Anastasia jokingly repeats her employer’s derogatory, classist, and possibly racist comment about a low-income housing project. Her dad is angry but turns it into a teaching moment and takes her to the low-income neighborhood where he grew up.

She has problematic faves. In Anastasia Has the Answers, Anastasia is obsessed with Gone with the Wind and has a crush on Clark Gable. Because she’s a budding feminist and has liberal parents, Anastasia will probably eventually notice the racism, sexism, and dubious consent in both the book and movie versions of that story. However, at least for now, she’s caught up in the romance. Our tastes don’t always align with our politics.

She acknowledges a “girl crush,” and her parents accept her completely. Also in Anastasia Has the Answers, our protagonist has a crush on her female gym teacher. Anastasia worries that her feelings are “gross,” and her mother assures her that these crushes are common and not gross at all. Maybe if this were written today, it would be clearer whether Anastasia feels attraction, admiration, or both for her teacher. Especially for preteens and teens, learning that you aren’t alone or shameful in your feelings can be life-changing.

Enjoy reminiscing about great fictional characters from children’s books? Enjoy some fictional childhood best friends and a peek at why the girls of The Baby-Sitters Club were like sisters.