The Enduring Ableism of LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER

Readers may be familiar with Lady Chatterley’s Lover, a Modernist novel by D. H. Lawrence, because it faced censorship and obscenity trials around the world. First published privately in 1928, it was not widely available in the U.S. and the UK until the early 1960s. It’s infamous for explicit sex scenes, and many readers consider it feminist for frankly depicting a woman’s sexual desires. Among disabled readers, it’s infamous for another reason: its ableism. As a disabled woman, I’ll never consider it feminist. A female, non-disabled character’s sexual liberation shouldn’t be at the expense of disparaging a disabled, male character.

Immediately after Connie and Clifford Chatterley’s honeymoon, he’s paralyzed in World War I. Many books from this period explore how physical and psychological trauma affected disabled veterans. Instead, Chatterley pities and dismisses Clifford, who “was shipped home smashed” (4). The novel calls him a ruined, inadequate man in various ways, dehumanizing him as “a hurt thing” (18). The central love affair is between Connie Chatterley and Oliver Mellors, the gamekeeper on Clifford’s estate.

One of the novel’s major themes is the tension between mind and body. The book depicts Clifford as purely intellectual because he’s paralyzed, contrasting him with able-bodied, working-class Oliver’s sexual prowess. Connie pictures her ideal lover “moving on beautiful feet” (201). On the same page, she describes Clifford as having “no real legs,” imagining him as a soulless creature with nothing but “cold will” (201). The novel dehumanizes Clifford at every opportunity because of his disability.

The novel uses Clifford’s disability to excuse Connie and Oliver’s affair — even for contradictory reasons. Ironically, Connie also uses Clifford’s paralysis as a cover story, contradicting her earlier remarks by saying her baby might be Clifford’s after all. Even Connie’s father suggests she take a lover, as if Clifford’s disability nullifies their marriage.

Social class is another important theme, but it’s difficult for me to parse from the novel’s treatment of sexuality, masculinity, and disability. Clifford is often contrasted with the workers in his mines, as if all miners are non-disabled. Mining is often dangerous and disabling work. Problematically, the narrative uses Clifford’s paralysis and sexual impotence to symbolize the ineffective, outdated aristocracy. It often conflates his entitled attitude and privilege with his access needs. If critical interpretations accept these biases unquestioningly, they compound the book’s ableism.

Many disabled writers before me have pointed out the ableism of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. In 2016, disabled professor and author Jan Grue wrote that the novel reflects an ableist belief — widespread in Lawrence’s time and persisting today — that disabled people are better off dead. Grue wrote that enjoying this novel “depends entirely on one’s capacity for literary identification — with Lady Chatterley’s erotic awakening, or with Mellors the gamekeeper’s forceful physicality.” Disabled readers, inclined to identify with Clifford instead, may find the ableism unbearable. He called Clifford “the very model of what Tobin Siebers critiqued as the Freudian caricature of a disabled person”: bitter, self-pitying, and one-dimensional.

Typical of Modernist lit, Clifford’s relationship with Mrs. Bolton is also Freudian. Bolton was Clifford’s childhood nursemaid. Connie hires her decades later as his personal care attendant, without asking Clifford first. This is a violation of his bodily autonomy. He considers his personal care an intimate aspect of his marriage to Connie. Mrs. Bolton infantilizes Clifford and is almost a maternal figure to him, but he’s attracted to her. She refers to what we’d now call Clifford’s PTSD as “male hysteria” (427). Despite their mutual attraction, the book calls an affair between him and Mrs. Bolton impossible. I could write a much longer essay detailing the blatant, constant ableism of this novel.

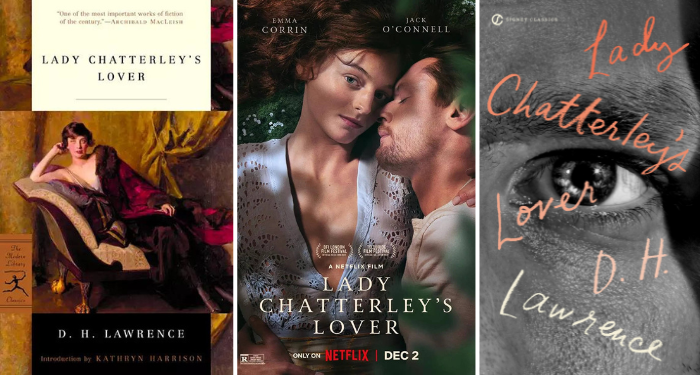

So, when I learned Netflix would release a new movie adaptation of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in December 2022, I was disappointed, but my curiosity was piqued. I thought it was a strange choice for a 2022 adaptation. It had been filmed several times already, from France in 1955 to the BBC in 2015. I was concerned when it was marketed as sexy and romantic. As Netflix rankings tend to prioritize early views, I waited several weeks to watch the film and pitch this article.

Ableism is integral to the story of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in a way that can’t be fixed. However, several changes made the 2022 Netflix movie safe for the actors and watchable to audiences today. Matthew Duckett, who plays Clifford Chatterley in Netflix’s version, is openly disabled. This is a positive change from previous versions with non-disabled actors playing disabled characters. Disability consultants and intimacy coordinators worked with Duckett to make the set and scenes accessible. Sex scenes and on-set accessibility must be coordinated carefully to ensure actors are safe and their personal boundaries are not violated.

The script also reflects some of these changes. The movie opens with Connie saying her wedding vows. Her words “in sickness and in health” seem ironic considering the rest of the story, and maybe that’s implied here. Connie asks Clifford not to hate himself and tries to learn how to assist him safely. Clifford says that only the first floor of his manor house is accessible to him now that he’s paralyzed. The book depicts Clifford as a burden, and the movie tries to rectify this, despite the ableist source material.

All the novel’s characters seem hateful to me as a 21st century reader. The movie eliminates most of the book’s casually bigoted language. Mellors seems much more romantic in the movie. In the book, Oliver confides to Connie that he physically and sexually abused previous partners. He says his wife and Clifford are both better off dead for impeding their affair. Connie and Oliver rarely even address each other by their first names, and he’s not the first man with whom Connie has an affair. The movie eliminates all these details, making it more appealing as a romance. Inevitably, though, any version of the story emphasizes Oliver as an athletic, able-bodied man with high sexual stamina, who can run and swim with Connie — unlike Clifford.

The ending of the movie is more romantic and less ambiguous than the novel. The book ends with Oliver’s letter to Connie, but it’s unclear if they’ll find each other. At the end of the 2022 movie, Connie and Oliver are reunited.

Some critics disliked these changes, which gloss over most of the novel’s critiques of classism. Mellors’s social status is much more scandalous than the affair itself. In the book, the Chatterleys even plot to pretend their artist friend, Duncan Forbes, is Connie’s baby’s father. Unlike Mellors, he’s the “right” social class. Some of the changes to the movie may be due to the time constraints of a short adaptation. By focusing on the romance over social class, the movie also eliminates some of the book’s ableism. Unlike Lawrence’s writing, the movie doesn’t frame Clifford’s paralysis and impotence as possible metaphors for patriarchy or aristocracy.

I understand why many people would never watch an adaptation of such an ableist book. I’ve always believed the film industry needs to adapt and produce more diverse stories. However, if filmmakers want to keep adapting classic and controversial novels, hiring diverse casts, crews, and consultants is necessary, and Netflix’s Chatterley did this well. Changing the source material can add new perspectives and avoid perpetuating some of the biases of the originals.

Check out more literary adaptations to stream or or another influential, banned work that had its own obscenity trial. For more on ableism and film, I recommend disabled filmmaker Dominick Evans’s 2016 blog post: “Hollywood Promotes the Idea it is Better to be Dead than Disabled.”