An Ode to Translator’s Notes

I’ve always been fascinated by the art and process of translation. I am also the kind of person who reads the acknowledgments before starting a book. So it’s no surprise that I’ve fallen head-over-heels for translator’s notes.

Not all translated works include translator’s notes, although the more of them I read, the more I miss them when they’re not there. I’ve come to see them not just as fascinating windows into the work of translation, but as crucial extensions of the actual work in question. Translator’s notes change the way I read translated fiction, to the extent that reading books without them, though I do it, feels incomplete.

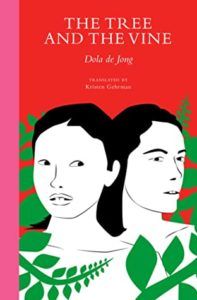

The first translator’s note I fell in love with is from Kristen Gehrman’s beautiful new translation of The Tree and the Vine by Dola de Jong. First published in Dutch in 1954, the novel is set in Amsterdam in 1938-1940. It follows Bea and Erica, two women who move in together soon after meeting. Bea, who narrates the novel, is in love with Erica but does not want to admit it. Erica, on the other hand, is careless to the point of recklessness, having affairs with other women, and often acting in ways that put her life in danger, especially after the Nazi occupation starts. The novel concerns their volatile relationship, and, as you might be able to guess, it doesn’t have a happy ending.

I read this novel in two sittings and knew it was something special. But even though I loved it, a part of me believed I shouldn’t. Here was another sad lesbian book from the 1950s that ends in tragedy. Haven’t we had enough of those? Then I read Gehrman’s translator’s note. This passage took my breath away:

“It’s easy to look at this story through the lens of war or to see it as a lesbian romance that could never be because of the restrictions of the time. But as I got to know Erica and Bea better, I came to see their restlessness, struggles, doubts, and hesitations as reflective of a broader female experience. The Tree and the Vine is one of the richest texts I’ve had the pleasure of translating and one that will stay with me.”

Gehrman goes on to quote Marnix Gijsen, a writer who championed the original publication of the novel. He said, it is “an important and remarkable book — and not because it addresses a delicate problem with so much understanding, that’s just the starting point. I’m more in awe of the finesse with which Dola de Jong sketches her two main characters.”

Gehrman and Gijsen articulated what I had sensed about the book but hadn’t been able to name upon finishing it. Yes, it’s a tragedy, but it’s a specific tragedy, a tragedy brought about the particular human hangups of the main characters, their desires and quirks and fears. Bea and Erica’s specificity come alive in the text; that’s what makes the book so good. And Gehrman is partially responsible for exactly how they come to life, at least in English. Her close reading of the text and the obvious care she took with its translation deeply affected my own reading of it. I believe I would have loved this novel if I hadn’t read her note. But I can’t know for sure. Her work is present in de Jong’s work, and I am grateful for it.

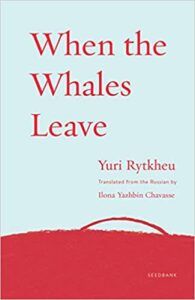

I had a similar experience, in a different order, reading When the Whales Leave by Yuri Rytkheu, translated by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse. When the Whales Leave is a gorgeous fable of a novel, beautiful, incandescent, and strange. Rytkheu was a Chukchi writer; the Chukchi are an Indigenous people from the Chukchi Peninsula in Eastern Siberia, on the Bering Sea, where the novel is set. It begins in some distant time at the beginning of the world. A woman, Nau, falls in love with a whale, Reu, and he transforms into a human to be with her. Their children become people, and thus humankind is born. The story follows Nau and Reu’s descendants through the years as the world changes around them.

I decided to read Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse’s translator’s note before diving into the novel. In it, she recounts a conversation she had with Rytkheu about her first translation of one of his books. Rytkheu wrote in Russian and his native Chukchi; he was also fluent in English. Chavasse recalls being worried about getting the translation right. So when she had the chance to talk to Rytkheu about it, she asked him if there was anything particular she should do or pay attention to. He told her to “write it like a song. Like you could sing it if you wanted to.” When they met again after the book was published, he told her: “In English, too, it sings.”

What a beautiful exchange. I was thinking about this idea, of a book that sings, when I turned to the first page of the story. Never in my life have I read a book that sings like this one. It’s a sad story. But it is also filled with glorious, musical language. The descriptions of the Arctic landscape are stunning. The words pulse with wind and sky and ocean and rock. It is so physical, so deeply connected to the stuff of the world. It’s like the words themselves grew out of the ocean, a translation of whale song and sunlight on ice and summer wildflowers on the tundra. It is, without a doubt, a song.

Reading about that conversation between Chavasse and Rytkheu gave me a deeper appreciation for the magic of this book. I would have loved it, and its breathtaking music, regardless. But not in quite the same way.

Earlier this week I started reading Deaf Utopia by Nyle DiMarco. The book begins with an author’s note which is also a translator’s note. DiMarco explains how the book came to be. He wrote it first in his native language, ASL, through a series of videos which he shared with his friend and co-writer Robert Siebert. Siebert translated those videos into English, and then DiMarco and Siebert worked together to hone and finalize the translation.

Because ASL and English are related, and because DiMarco is fluent in both, I had assumed Deaf Utopia was written in English. The author’s/translator’s note not only deepened my understanding of the book; it expanded my understanding of translation in general. Once again, I was struck by just how important this short note at the beginning of the book proved to be. Without it, I would have missed something essential about DiMarco’s story.

All of these translator’s notes I’ve mentioned — and many more that I’ve read and loved — offer a lot more than context. Chavasse, for example, writes about how many weather words appear in When the Whales Leave, and how many words for sunlight, and the joys and challenges of translating those concepts. DiMarco explains the kind of ASL gloss — a written approximation of ASL signs — that he and Siebert chose to use in book. The best translator’s notes are both emotional and technical. They’re not optional afterthoughts. They are vital pieces of translated books. They don’t just provide insight and context; they provide essential information about the strange and complicated process of moving meaning and beauty from one language to another. It’s time we start giving them the attention they deserve.