How Reading Sir Terry Pratchett Helped Me Through My Depression

CW: Mention of suicide attempt

In my younger years, my mother was a school librarian. Which meant that after school and homework was done I would be free to peruse the stacks and read whatever I wanted to my heart’s content. Up until my sophomore year of high school, as an awkward kid with no social skills, books were really my only friend.

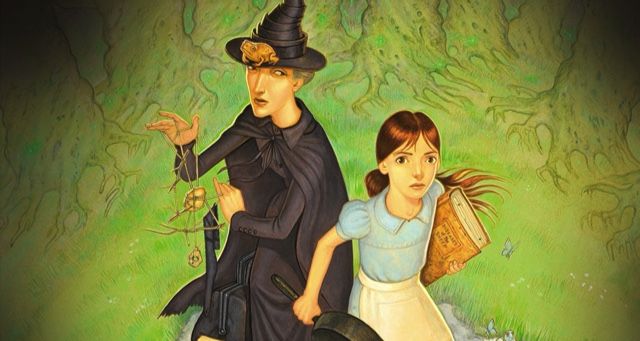

This is how I came across the good Sir Terry Pratchett. Ironically, it was not in my mother’s library that I found him, but rather one of the public libraries nearby. I was your typical angst ridden 12-year-old, my depression and bipolar disorder just starting to appear as these things do with puberty. I found my first book by him while prowling the young adult section, looking for a book I hadn’t read yet, but also wasn’t one of those coming-of-age sappy romance books that I refused to acknowledge at that age. I came across his book The Wee Free Men, about a girl named Tiffany full of righteous anger and selfishness, armed with a frying pan and a tribe of little blue men, who fought to save her little brother (who she really didn’t like that much) from the faerie queen because he was hers and you protect what belongs to you. Because, in words taken directly from the book:

“All witches are selfish, the Queen had said. But Tiffany’s Third Thoughts said: Then turn selfishness into a weapon! Make all things yours! Make other lives and dreams and hopes yours! Protect them! Save them! Bring them into the sheepfold! Walk the gale for them! Keep away the wolf! My dreams! My brother! My family! My land! My world! How dare you try to take these things, because they are mine! I have a duty!”

“All witches are selfish, the Queen had said. But Tiffany’s Third Thoughts said: Then turn selfishness into a weapon! Make all things yours! Make other lives and dreams and hopes yours! Protect them! Save them! Bring them into the sheepfold! Walk the gale for them! Keep away the wolf! My dreams! My brother! My family! My land! My world! How dare you try to take these things, because they are mine! I have a duty!”

As I got older and my mental health got worse, I continued to read the Discworld series. I grew up with Tiffany and watched as she didn’t become less emotional but instead used her emotions to solve problems, some of them problems she created, and make life better for people, even if they weren’t appreciative. I met Granny Weatherwax, who said you should never be afraid of what’s in the woods because you should be sure that you’re the scariest thing out there. But most of all, I met hope, the idea that things would get better even if you have to be the one that makes them better, dragging the darkness kicking and screaming into the light because, as Pratchett says in Men at Arms, “Sometimes it’s better to light a flamethrower than curse the darkness.”

It was this idea of hope that kept me going as my depression and anxiety tried to take over. On days when it was a struggle to get out of bed, when my brain was actively worked against me, asking me what was the point of it all, why even bother, simultaneously turning everything gray and making it too much at the same time, I would remember Tiffany Aching kissing the winter and returning the world to summer, Eskarina deciding she wouldn’t be a witch or a wizard, but something in between (which was a lightbulb moment when I realized I was nonbinary), I would say to myself if they can do that, I can get out of bed. I can brush my teeth. I can go to that party, and if something goes wrong, then it goes wrong, but that’s okay, because I’m the scariest thing out there. Sir Terry Pratchett and his characters provided me with my idea of hope and justice and love and truth (and a hard boiled egg). I am not sure who I would be without him guiding me helping me learn how to be brave and think for myself while making me laugh.

However, this isn’t to say he and his books cured me, or that he fixed everything for me. That would be wishful thinking and foolish. Books and stories can do many things, but they can’t make your choices for you and they make others kinder for you as well. I still was bullied throughout middle school. I still entered into an abusive relationship in high school and didn’t understand the scope of what was done to me until years after I left it. I still attempted suicide a couple times and hurt myself, because my neurochemicals were out of sync and no story can fix that. I still had to start medication and start therapy to work past that mess of neurochemicals and trauma, but Sir Terry Pratchett’s stories made it better and a touch more bearable. He was reliable and always there, even when my brain wasn’t. He made sure I always cared about something because, as he said in Reaper Man, “All things that are, are ours. But we must care. For if we do not care, we do not exist. If we do not exist, then there is nothing but blind oblivion.”