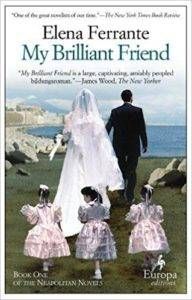

Rereading Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend Ahead of the New HBO Adaptation

Guys, I am so hype for the HBO adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend. So much so that I did something I rarely do: I reread the first book of the series! (I don’t usually reread books because I feel bored since I know what’s going to happen, and I’m generally anxious about the new books I am not reading, which is maybe a topic for another post. If you’re interested, I wrote a round-up of books I found similar to the series a while back, which you can read here.)

I have some scattered thoughts about rereading this book though, which I would love to hash out a bit in the comments if anyone has any extra thoughts! I can’t promise a super linear post because these are just things that popped up while I was reading. (Do not read this post if you don’t want to be spoiled! Also it mentions some sexual violence, general physical violence, and some ableism.)

Firstly, this book still strikes me as such an amazing description of coming into womanhood—the fluctuations in confidence to do with beauty and smarts, the realizations of what a womanly body means to men, the insufferable competition between girls we are taught to perform. Lenù’s insecurities are at first about whether she can be loved by a man because she does not find herself attractive, while Lila, sharp and generally ahead of Lenù, is immediately aware of how women can get hurt by men in the neighborhood and beyond. In rereading this book, I can see how Lenù is naive and innocent, and Lila might seem aggressive and overtly violent, but it’s so obvious that Lila knows more about the world than Lenù. Still, Lenù’s struggle with her sexuality after she is sexually assaulted by the Donato Sarratore feels incredibly real: survivors often confuse sexual desires and disgust for what was done to them, and these feelings can be even more confusing if, as a young woman, you don’t really understand what was done to you. Ferrante writes about the violence of men responsibly and accurately, and that current of violence is always underneath the storyline, waiting to rear its ugly head either as a strike or as trauma.

Another thing I was also very aware of, this time around, is that Lenù’s perspective of Lila might be extremely distorted (or, in the least, framed by how much Lila will reveal to her). Lenù suffers so much because Lila doesn’t share enough with her, but she herself keeps her vulnerability close to her heart. I found myself more willing to be empathetic towards Lila—after all, though both of their parents suck, Lila is the one left without an education when she could have thrived—and her violence, the learned violence of the neighborhood this time around.

So much has been written about how Ferrante’s novels capture the complexity of friendship between women, and I certainly think that’s accurate. However, sometimes it’s difficult for me not to think about how gay their relationship can be—maybe not sexually, but romantically for sure. Lenù describes so many moments where she feels compelled to be around Lila, and how the only motivation she can find to study is Lila’s friendship. She studies not for school, but to be able to impress her friend, have deep conversations with her. I can’t help but think there is at least some romantic feeling there—after all, Lenù sometimes says similar things about Nino Sarratore—and that all the anger and falling out in later years is somewhat due to the fact they could never properly indulge these feelings.

On a negative note, I also noticed how much Ferrante uses Lenù’s mother’s disability to paint her as unhappy and mean. Honestly, since I was made aware this is a trope in literature, I don’t think it should ever be given a pass. Though Lenù is a child and a teenager for all of this book, and perhaps her perspective is ableist in itself, it’s really cringe-worthy and plainly offensive that her mother’s bad character is always related to her limp.

I hope the HBO adaptation retains all the good parts of the series and is reflective about the harmful parts of it. The previews I’ve seen look incredible, and HBO hired Neapolitan actors to play the main characters. An interesting thing about it is that even Italian viewers will need subtitles, since the neighborhood dialect isn’t understandable to all Italians. I’m impressed by how HBO seems invested in retaining authenticity (and refrained from Americanizing the series) and cannot wait to see it.