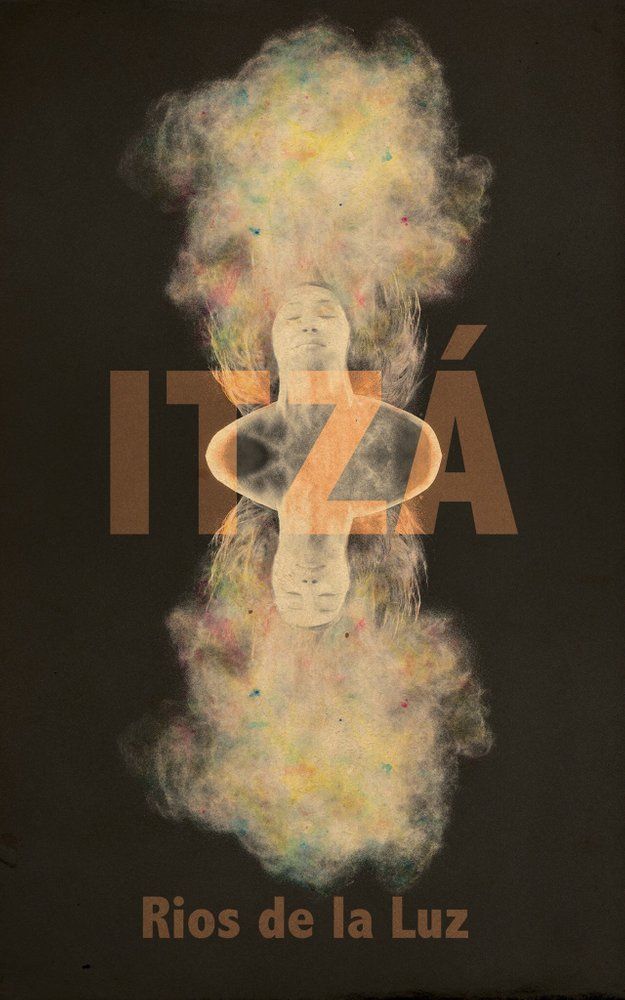

ITZÁ: The Pain and the Power of Brujería

I stopped.

For a week it sat on my nightstand until I could meet it again. Then I sat down and read a few more chapters, and again had to pause in order to shore up my strength to keep reading. Rios de la Luz did not pull any punches.

Recently, I’ve been introduced to a number of indie and small press books by fellow Latinx persons. While yes, I present as white, there’s a lot to be desired in Latin representation in the publishing industry. The refreshing thing about small press books by Latinx people is the sublime rawness of the ones I have come across. Perhaps it’s just perception, but these books seem to have less editorial censorship. Issues, language, ideas and the very depiction of events aren’t rewritten to make them palatable for a white audiences.

Itzá is not censored, nor does it hold itself back. It follows generations of water witches, shifting through time and narration while doing so. The book itself is a difficult read—not only because of its subject matter, but also because the language is deliberately poetic. The narrative moves around, and with short chapters, the focus jumps from one anecdote to another in rapid succession. It’s difficult to parse what is lyrical embellishment, what are fantastical elements, and what is “real” to the story. But the result is wonderfully organic, beautiful, and heart-aching.

The language that de la Luz employs serves to reflect the liminal experiences in the book. We are meant to be disoriented, meant to be spoken to and to also fully embody the experiences of the characters when she switches from first person to third.

“What do you mean when you call someone illegal? What do you mean when you call brown children a threat?”

“What do you mean when you call someone illegal? What do you mean when you call brown children a threat?” She writes in one instance. It is what one of the grandmothers says as she interrogates white politicians, torturing them in the Gulf of Mexico. Does this superhuman grandmother actually kidnap these men? Or is it a child’s imagination? Is this an accusation to the reader?

Perhaps it is all a fantasy? De la Luz’s characters seem to sometimes exist in our collective psyche and revenge fantasies. Or even still, in the world of the narrative, are these water witches acting out on lifetimes of racism and sexism with their magic?

I quite obviously love this book, even though it causes me so much pain to read it. Some chapters are reminders of trauma that is difficult to discuss or process. The traumas of sometimes growing up as a Latina in a country that wants to disown you are especially painful. How do I tell you about being screamed at as a child for not speaking English by adult strangers? How do I tell you of the very real desire to connect with your culture, but the ever present lure of whiteness? While I was never raped (as one of the characters here is), how do I tell you about violation? How do I tell you of the desire to close off your body to everything afterwards?

For the women in Itzá, the answer lies in witchcraft, in the surety of their power. The book has reoccurring themes of body manipulation and in the creation of rituals to deal with trauma. These rituals are grotesque at times—like the collection of snot as a sacrifice. Other times they are painful, like taping duct tape all over the body. The rituals can be unhealthy, but they can aid in dealing with the pain, giving order to an uncontrollable world.

Looking back at my own childhood, I see the rituals I used to cope with pain. Rituals that haunted me and moved into adulthood. I look back to other women in my life who have lived a similar existence. I see the things we have done to survive, the phobias we have inherited, the eating disorders, the superstitions and on.

De la Luz gives a messy, real language to our lives. When I go through the book, I can see the things a book published by a larger house may have had to change. There are areas that are unclear. There are passages which are so thickly coated in poetic language that are often obscure on truth, but acute on sentiment. What a shame it would have been to clarify those sentences, to make them bland and flavor less.

Instead, what a gift it is to have this book, full of the mess of pain and trauma, that we may then learn to turn our broken words into spell craft.