Situating (White) Women’s History In The U.S. Within Its Context

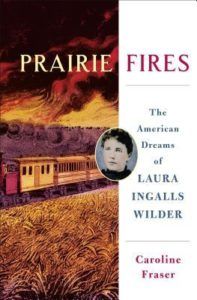

I knew what I was reading, and I read a lot of smart commentary on the books following that experience. And with the publication of Caroline Fraser’s Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder, I was eager to see her story put into context of the westward expansion (and subsequent impact on Natives).

Prairie Fires begins with talking about how Natives were forced from their lands illegally. About the ways they were impacted by whites taking over their land. About the ways the U.S. government treated them terribly. Fraser doesn’t shy away from the bloodshed, and she doesn’t shy away from explaining the racist beliefs white settlers carried with them. There is no apologizing for it and no ignoring it. We know going into the biography that there was no excuse for it, and yet, we’ll see it again and again throughout the biography, much as we’re exposed to it in the series.

And it’s not racism solely against Natives.

While listening to Prairie Fires, I was reading Winifred Conkling’s new young adult nonfiction book Votes for Women!: American Suffragists and the Battle for the Ballot. This isn’t the first young adult nonfiction title I’ve read about women’s history and the suffragists, but it’s perhaps the first which looks at the complexity of the women who were pivotal in the movement.

But rather than hold these women up as worthy of unfettered adoration, Conkling does not shy away from showcasing how racist they were. The push for women’s suffrage happened during the same timeframe that the abolitionist movement happened, as well as the same time that the temperance movement occurred. Anthony and Stanton, and indeed other ladies of the suffrage movement, were not shy in expressing how disgusted they were thinking about black men—who they saw as uneducated, dirty, and less-than-human—should earn the right to vote before white women—educated, clean, classy, fully-human. They actively threw other movements under the bus in order to push forth their singular agenda of rights for white women before anyone else.

These two books—Prairie Fires and Votes for Women—are situated in the same historical period of America.

Conkling’s book digs into how America finally granted (white) women’s suffrage, showing how states in the west were among the first to grant the rights via their state constitutions. Missouri, where Laura Ingalls Wilder was during this time, was one of the most challenging states; as Fraser wrote, while the state fought on the side of the Union in the Civil War, records show that slavery was alive and well. Rose Wilder Lane, Laura’s daughter, despite being given tremendous freedoms thanks to the work of the suffragists—her own income, the ability to divorce her husband, means of traveling as a single woman without a companion—did not care for the movement nor consider herself one to advocate for suffrage.

Reading the two books in conjunction provided a context neither could alone. And more, reading the two books in conjunction highlighted the fact that the idols of white American ideals—manifest destiny, women’s rights, pulling oneself up by the bootstraps—are pockmarked by racist beliefs and trails of blood of those who’ve been stepped on, spit on, and ignored again and again.

Both Fraser and Conkling’s books, much as they look these problems head on and don’t shy away, don’t quite go far enough. Conkling talks about Sojourner Truth and Fredrick Douglass, but few other activists of color are mentioned in the book. Fraser, by virtue of writing a book about Wilder, offers little in terms of how Native women at the time were surviving on the prairie and how they were surviving despite the fact their lands were being stolen, their rights being cheated, their lives being utterly destroyed because of white women.

But these books are a start. And more, they’re a start for white women like me, raised on the “history is told by the winners” history mentality that’s far too common. These books pull the curtains back, showing the less-sightly parts of the women we were raised to believe needn’t be questions or examined in such a way.

It should not be refreshing to read women’s history books like this. It should be the norm. And more, should be the start of a long reading trail, filled with the voices and stories of those who look nothing like us, who history has pushed to the margins, and who have been there all along, even when we’ve selected to ignore, forget, abuse, or steal from them.