The First Novel I Read Every Year

For the most part, I am a one-and-done reader. I can live in the pages of a book fluidly and easily, embracing the warmth and coldness it has to offer as if I created them myself. When I turn the final page, I rarely revisit the actual book itself. The words, of course, stay with me and I often find myself still living within their warmth for days on end, reconsidering and reimagining.

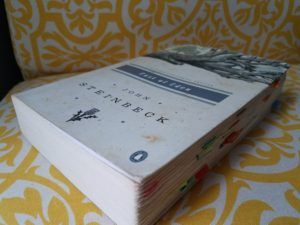

There are, however, a handful of books I find myself unable to resist opening over and over again. The pages of these books don’t simply offer a temporary stay as the others do. They feel different. Their words taste different. More mine. I’ve read Night by Elie Wiesel, a handful of times. And though it has only been out for a year, I’ve read Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi twice and feel compelled to revisit it already. The Princess Bride by William Goldman is simply a guilty—and beautifully versed—pleasure. But, John Steinbeck’s East of Eden is the only novel I read religiously each year. I’ve been asked why many times, and as my fingers drum the endless sticky notes that fill the pages of my copy and my fingers trace the words I’ve been underlining for years, I can only answer instinctually: because I have to. It is necessity more than habit. Nourishment more than craving.

“But I have a love for that glittering instrument, the human soul. It is a lovely and unique thing in the universe. It is always attacked and never destroyed – because ‘Thou mayest’.”