An Invocation for Writers: May Your Work Be Banned

Leaves of Grass. Beloved. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Fahrenheit 451. The Color Purple. Native Son.

Classics, right? Yes. But also: these are books that—at one time, and many of them still—straight up pissed people off.

They challenged common notions of propriety and sexuality; they called systemic racism to task; they highlighted the humanity of people whose humanity those in power thrived on denying. They spurned censorship. They asked us to be better. They saw everything and demanded much.

That’s what makes literature great; it is also, too often, that which leads to pyres and angry parents and petitions to library boards, among other kinds of book bans.

Banned Books Week exists to highlight the bravery of art like this. It serves to remind us how much is at stake when we choose silence and complacency over speaking truth to power. It asks us to absorb and stand up with marginalized voices and unpopular opinions; that’s where our best, richest future lies.

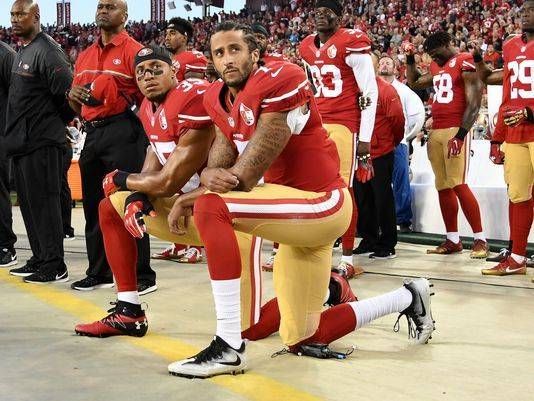

This Sunday, as Banned Books Week began, it struck me as congruent that, across the nation, athletes were taking a knee in protest. That’s certainly not what many of their audiences wanted. They wanted to be entertained, not challenged. Those with the most power invited the action by calling football players too “soft,” and slurring Colin Kaepernick, the first player to take a knee in protest of police violence.

It is brave and necessary and lonely to take a stand against very powerful people who have a vested interest in your silence, but it’s what great artists—from athletes to writers—do. Starting Banned Books Week with the image of teams kneeling across the nation felt powerful and meaningful. Players had the option not to follow Colin Kaepernick’s example, especially after the president of the United States opted to slander him publicly; they chose, instead, to follow suit.

Readers, too, have the option not to follow writers into the fray: to hear that challenged books are “dangerous,” and to pick up something else instead. Something safe. Something easy. It’s as unappealing to be thought of (in various ages) as a socialist—or a hippie or another form of “radical”—based on your reading material, as it is to be thought of as unpatriotic because you did not stand for an anthem.

Yes, it’s easier to pick another title; it’s safer to go another way. But Banned Books Week endures because enough readers don’t want to be safe, or coddled, or eased away from reality; they want to be challenged, to see the world through someone else’s eyes, to empathize with those with drastically different life experiences. To read toward change. To welcome another viewpoint, to look up from a book and see a widened world, and to say, “what’s next?”

We’re living in dangerous times. People want us to be quiet. They want us to stand still and put our hands over our hearts and look straight ahead and pretend gross injustices aren’t occurring in the periphery. They sure don’t want us to look at the injustices straight on and name them.

But we’re not all complying. We’re taking knees. We’re taking to the streets. And I have to believe, this Banned Books Week—have to hope, have to know—that somewhere off stage, someone is writing something powerful that’s going to call all of those in power to task for what they’re perpetuating.

Somewhere, words are going down on paper that will be banned. And that’s a glorious thing.

There’s an uncomfortable onslaught that comes with being banned, sure; for a while, at least, those wedded to the status quo feel comfortable declaring you the enemy. But the life of a book that’s been banned (or of words spoken in protest, or of an image of a fist raised in defiance, a knee taken in solidarity) is so much longer than that of a book that asked little of anyone. The lines and pages and volumes that stick and stay and thrive are those that ask the most of us.

There’s a power in banned materials, phrases, and sentiments that can’t be equaled, and that’s worth striving toward. Art should challenge all of us, but especially the institutions that ask it to be “safe.”

My wish for all writers is that they produce work strong enough that it rubs someone small the wrong way. May your work call out the worst in us. May it demand more of the culture it responds to. May it lead to change.

I think that’s the best we can wish for any title: may it someday be banned, for all of the right reasons.