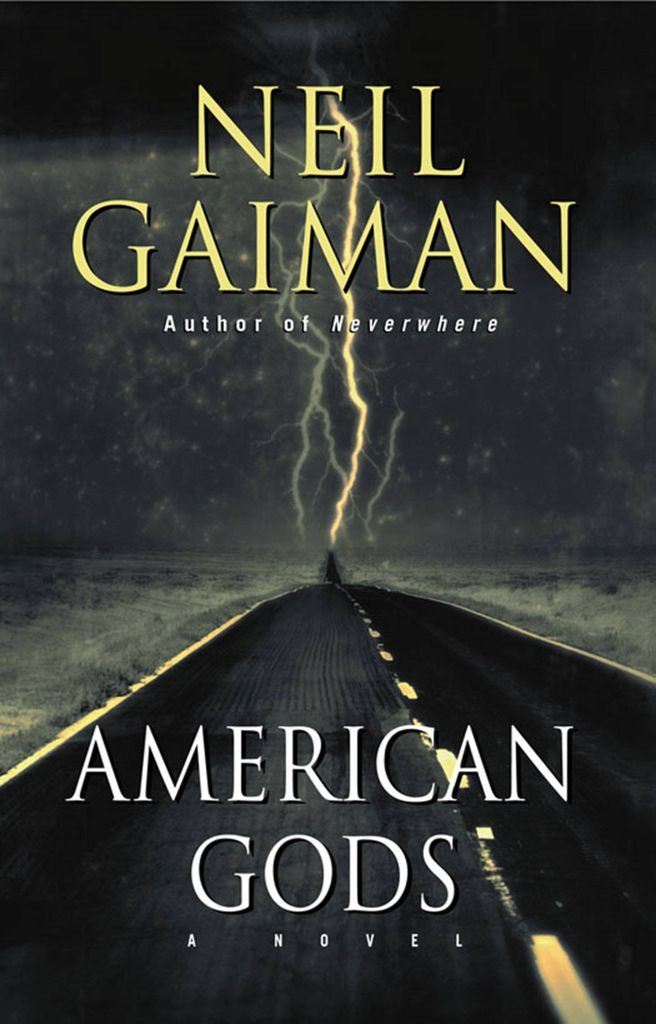

Before AMERICAN GODS, Gaiman Explored the Brief Lives of Gods in THE SANDMAN

After months of anticipation, the television adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s beloved novel American Gods premieres this Sunday on Starz. The novel—and soon the series—explores the lives of centuries old gods trying to get by in a world that no longer needs them. It’s a brilliant concept, one that opens up nearly limitless storytelling possibilities.

American Gods was not the first time Gaiman explored these ideas, however. Several years earlier, the “Brief Lives” arc of Gaiman’s The Sandman comic series built a similar mythos of gods trying to get by long after they’ve been forgotten.

For those of you not familiar with it, The Sandman tells the story of Dream, one of the seven Endless, personifications of essential concepts that have existed since the beginning of the universe (his six siblings are Destiny, Death, Destruction, Desire, Despair, and Delirium). Over the course of the series, Dream interacts with people, nightmares, angels and demons, and, of course, gods.

The Sandman #45, art by Jill Thompson, Vince Locke and Daniel Vozzo.

The gods in Sandman will feel immediately familiar to anyone who has read American Gods—and vice-versa. They were created from the collective dreams of humanity centuries earlier, but now find themselves leftovers from largely forgotten pantheons, trying to find a new niche to justify their continued existence.

The Sandman #45, art by Jill Thompson, Vince Locke and Daniel Vozzo.

What happens to old gods when their worshippers disappear? “Some of them die. Some of them change. And some of them just keep going. Maybe some even get jobs as dancers.” Gaiman’s gods take jobs as lawyers, as corporate mavens, and, yes, as erotic dancers.

Many of the gods portrayed in Sandman feel particularly familiar. The Mesopotamian fertility goddess Ishtar, for instance, bears a striking resemblance to Bilquis in American Gods, both of whom have turned to sex work to find modern worshippers. We also see the Egyptian cat goddess Bast, and hear news that Marilyn Monroe is now a member of the Japanese pantheon.

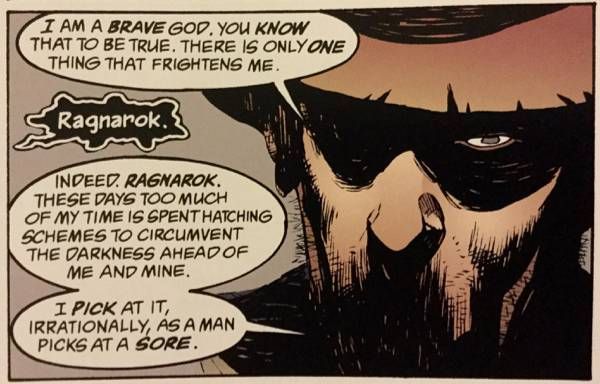

But, most familiar of all is Odin. Gaiman’s Odin is not the honorable, albeit easy-to-anger Allfather of Marvel Comics; instead his is a conniving, conspiratorial Odin who you can believe would become blood brothers with Loki. When Odin first appears in the “Season of Mists” arc, he is plotting with Loki how to trick Dream out of Hell, the most desirable piece of real estate in the cosmos. This Odin has a single worry: Ragnarok and the mortality it promises to bring with it.

The Sandman #26, art by Kelley Jones, George Pratt, and Daniel Vozzo.

Unsurprisingly, there are remarkable similarities to Mr. Wednesday in American Gods, who spends the novel running a long con to increase his own power and extend his own life, at the expense of everyone around him. But they are not entirely similar. While Sandman‘s Odin resides firmly within a traditional Norse pantheon, Wednesday is an American god, bereft of worshippers and relying on con games and scams to get by.

Ultimately, American Gods feels like a novel-length exploration of these ideas, told via a roadtrip to some of the United States’ oddest locales. By expanding on the ideas first developed in The Sandman, we get a much better insight into what it means to be an aging god in a secular age. Where Sandman offered only brief vignettes of a few gods, American Gods fills its world with richly-drawn characters full of history.

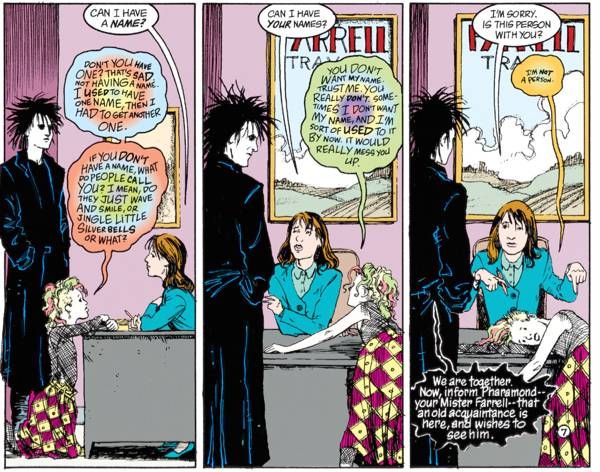

But while American Gods excels at these sorts of character moments, it never feels as compelling or essential as the “Brief Lives” arc of Sandman that served as its inspiration. “Brief Lives” benefits from the hilarious and heartfelt team-up of Dream and his sister Delirium, who are on a road trip to locate their long-lost brother, Destruction. The pair make a classic comedy duo, with Dream playing the straight man to Delirium’s often hilarious insanity.

The Sandman #43, art by Jill Thompson, Vince Locke, and Daniel Vozzo

American Gods, by contrast, suffers greatly from a central protagonist, Shadow Moon, who is written as a cypher. Gaiman keeps so much about Shadow hidden until late in the novel—his multiracial background is first mentioned obliquely near the end of the novel, for instance—that it is extraordinarily difficult to feel a connection to him.

Reading “Brief Lives,” I cared about whether Dream and Delirium find Destruction and whether the gods they meet along the way survive to live another few millennia; reading American Gods, I could not really bring myself to care whether Shadow lived or died. This is not to say that I think American Gods a bad novel; it is expertly written, with some genuinely creative sequences that would stand out in any book. But, it’s hard to escape the sense that Gaiman already wrote the definitive treatment of down-on-their-luck gods several years earlier.