NOT NOW, BERNARD: A Children’s Book of Existential Dread

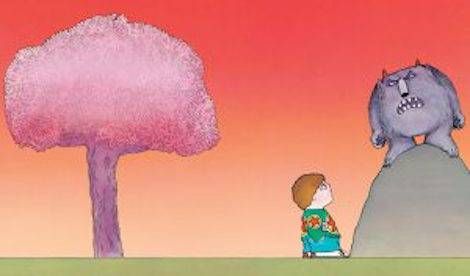

Not Now, Bernard by David McKee

I was recently reminded of a book from my childhood: Not Now, Bernard. I’m not sure how it affected me then, but looking at it now, it is terrifying! Not in the ‘boo’ jump-scare way of modern horror, but in the sinking-feeling-in-the-pit-of-your-stomach-as-you-realise-there-is-only-a-void-beneath-your-feet way. Like watching Von Trier’s Melancholia and realising that all is essentially futile, as human cruelty and kindness is indiscriminately destroyed in a planetary collision. I’m sure everyone has experienced something similar. You’ve all read something that has instilled existential dread at the meaningless of life in you, right? Maybe it’s just me. Maybe I’m over exaggerating. But have you read Not Now, Bernard?

Not Now, Bernard is a slender picture book for children aged 3-5. First published in 1980, it remains a perennial favourite. For me, it is what you might have got if H. P. Lovecraft turned his hand to writing books for children, where the universe is a cold and indifferent place that contains monsters.

In the book, a young boy, the titular Bernard, repeatedly tries to alert his parent’s to the monster in the garden. Unfortunately for poor Bernard, they are distracted, inattentive, and too busy, and just repeat the refrain “Not now, Bernard.” This would be bad enough in itself, the basis for a moral tale of parental neglect, but what happens next is terrible. Bernard decides to go out into the garden, and is promptly eaten by the monster – trainers and all. The monster then goes into Bernard’s house, and proceeds to wreak havoc. However, his behaviour is only met with the response, “Not now Bernard,” until eventually the monster is tucked into bed and the lights are switched off. The book ends with neither parent aware that their child has been devoured.

The knee-jerk reaction would be to protect our children from such terrors. We might become the reverse of Bernard’s parents, the gatekeepers of literature and media. However, as a child I don’t remember being frightened by such stories. I thrived on the slightly twisted, darker narratives of Dahl. Perhaps I was too young to be troubled by the nihilism of Not Now, Bernard. It is my adult awareness of contemporary trends, and my concern at the seemingly indifferent attitude authority takes to the vulnerable, that makes the book seem so troubling now. We bring ourselves to whatever we read.