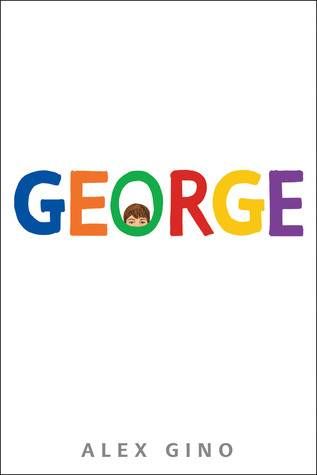

Why I’m Reading GEORGE to My Kids

Today is The Human Rights Campaign’s National Coming Out Day, and to celebrate we are spending the day featuring LGBTQ+ voices. Enjoy all the posts here!

If you’re unfamiliar with it, George is about a trans girl in 4th grade. Melissa knows she is a girl even though everyone sees her as a boy. Through the book, Melissa tries to figure out how she can explain who she really is to the people in her life: her teacher, her best friend, her mom. It’s a tall order for a child, but Melissa really does understand herself and is able to give young readers context and vocabulary around gender identity. The 3rd person narration also refers to Melissa with she/her pronouns to validate that identity.

Here are a few reasons why I decided to read George now instead of later.

- One of my children is very gender conforming. The other is not and never has been. It’s important to me that both of them see gender in a broader way. My gender-essentialist kid needs their view expanded so they don’t exclude or tease others. My gender-nonconforming child needs to know that there are many different kinds of gender identity so they can feel comfortable finding theirs.

- The world is full of trans and nonbinary people. I don’t want a pleasant interaction with a friend to turn into an object lesson when my kids label a friend as different. They’re my kids, so covering Gender Identity 101 should be my job.

- Reading George reminds me of the many ways parents impose gender essentialism on their kids. In the book, Melissa’s mom loves her a lot and is usually a kind and caring parent. But she also hurts her constantly by her regular use of masculine words to describe Melissa. At one point, Melissa is considering telling her mother about her identity and seeing Melissa has something on her mind, her mom says, “Whatever happens in your life you can share it, and I will love you. You will always be my little boy, and that will never change. Even when you grow up to be an old man, I will still love you as my son.” In trying to say the right thing to her child, Melissa’s mother says so many wrong things that Melissa decides not to confide in her and only feels more misunderstood. I don’t want to reinforce gender stereotypes around my kids, and I want them to develop their own identities without pushing them towards a masculine or feminine ideal.

We are close to the end of the book and my kids, often tight-lipped, are quiet as usual as we read each night. But sometimes after a chapter where Melissa’s thoughts and identity are discussed in detail, I say to them, “Do you understand what that meant?” and they shake their heads. That is when the real conversations start.

We have talked about bodies vs. how you feel inside. We have talked about how bodies can be changed or kept the same. We have talked about boys and girls and people who feel like neither of those things. It is usually a short conversation. We chat, brush teeth, climb into bed. The next day we read again and they have less questions.

Initially I was a little worried. The first chapter has references to masturbation and pornography, not direct ones but they’re there. I wondered if we’d started too early. But the kids did not blink and I remembered that before this we’d read Mary Poppins, which was full of words they did not know and things they did not understand. (Honestly, there was a lot in that book that I didn’t understand, either.) If I’d had a bit of foresight, though, I would’ve thought to have us read George right after reading Charlotte’s Web, since the stories are tied together.

I do recommend that parents read George before reading it to their children. It’s less about screening for content and more about knowing in advance how the story is presented and when you may want to ask your children for their thoughts and questions.

We live in a complex world, and so do our kids. We need to talk about race and poverty and sexual orientation. Likewise, there is no reason to hide gender identity from children. School-aged children are not “too young” to discuss gender identity. Trans and nonbinary children exist and they have to grapple with these issues. My kids may realize one day that they identify as trans or nonbinary. They may find roles as allies to trans friends. These aren’t adult issues. So far my kids have accepted Melissa for who she is. They are invested in her story. And that’s just as it should be.