An Ode to Bookish Moms

When I was five, we lived in Singapore, with an amazing public library across the block. Since I read books faster than my parents could put them in my hands, my mother and I used to frequent the library once a week. I had my reading spot near three rows of Enid Blytons, and was tearing through all the Noddy books, and my mother had the same sort of bond with Jeffrey Archers and John Grishams at the time. When my brother was born, neither of us were going to give up our library trips, so my mother used to take us both to the library; him in his pram, me walking alongside. Once we were done picking and issuing our books for the next few days, we’d face the task of transporting ourselves and our books back home. My mother’s solution was brilliant: our (many) books would go in the pram, she would carry my baby brother, and we’d trudge home.

When I was 8, we’d moved back to India, where public libraries were few and far; there were none in our vicinity to my disappointment. My school had a decently-stocked library, but there was one problem: our librarian couldn’t be bothered to keep up with my reading sprees. ‘One book a week’ was the norm she had invented, mainly because books were either returned to her in bad condition, or worse, never returned. I pleaded with her to let me borrow more than just one book a week, but she did not relent. Helpless, I told my mother about this, and at our next parents-teacher meeting, she asked my English teacher why our schools had such rules. My teacher in turn spoke to the librarian, and I was allowed to borrow books from the school library as and when I pleased thereafter.

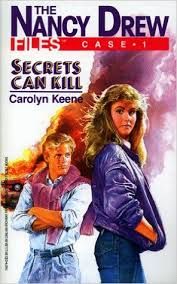

When I was 10, a friend borrowed a Nancy Drew from me. When she returned it, it was covered with newspaper. I asked her why she did that, and she said her mother didn’t like her reading anything that wasn’t for school. I was extremely perplexed.

‘But

‘Yes, but she disapproves of anything which doesn’t look literary. And especially with that cover…’ she trailed off. I was horrified. I couldn’t fathom a mother declaring a book inappropriate. And what was wrong with the cover? Was I making wrong reading decisions? Since my mother had never really declared a book unsuitable for me, I just assumed that reading of all kinds was an activity that was encouraged.

When I was 14, I remember going through Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in around 12 hours, and promptly handing it to her. I made her abandon whatever work she was doing, sat her down, and fluttered around for the next two days, until she’d finished reading it. I needed to rave and rant and sob and share, and I needed to do it with her.

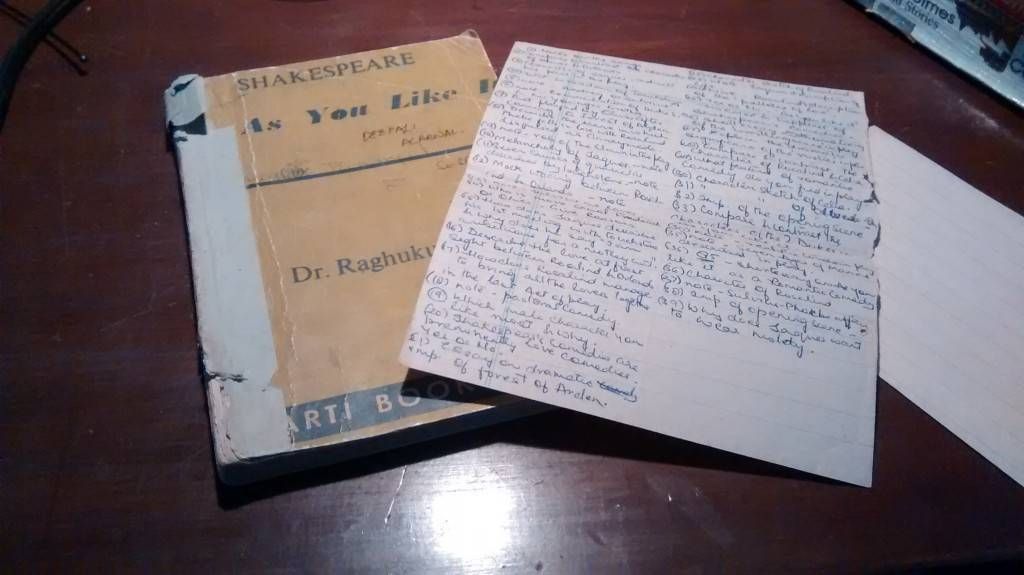

In my second year of my BA degree in English Literature, we had As You Like It as part of our Shakespeare paper. I wasn’t really getting into it, and one afternoon I had a flash of memory. I’d seen my mother’s old copy of the play in a cupboard somewhere around the house. I scoured through some shelves to unearth it, and opened it to find a sheet of notebook paper tucked neatly into the book; her notes on the play:

I abandoned my brand new copy of the play, and used hers for the entire semester. As weird as it may sound, it helped pique my interest in the play.

My birthday gifts have been books since I can remember: just last week, I was ordering a bunch of books online and simultaneously mourning my empty wallet, when she told me not to fret: ‘why don’t you consider those birthday gifts from me?’ When I protested, she said ‘okay, then, add some more to that list, because I can’t think of anything else to get you.’

It’s an extremely nice feeling, knowing exactly where your love of books comes from: from being read bedtime stories from a giant blue book with a moon on the cover, to coming home and finding her sitting with her reading glasses on, reading.