As Soon As He Returns

This is a guest post from Nicole Mulhausen, who tends a large garden and reads and writes in the maritime Pacific Northwest.

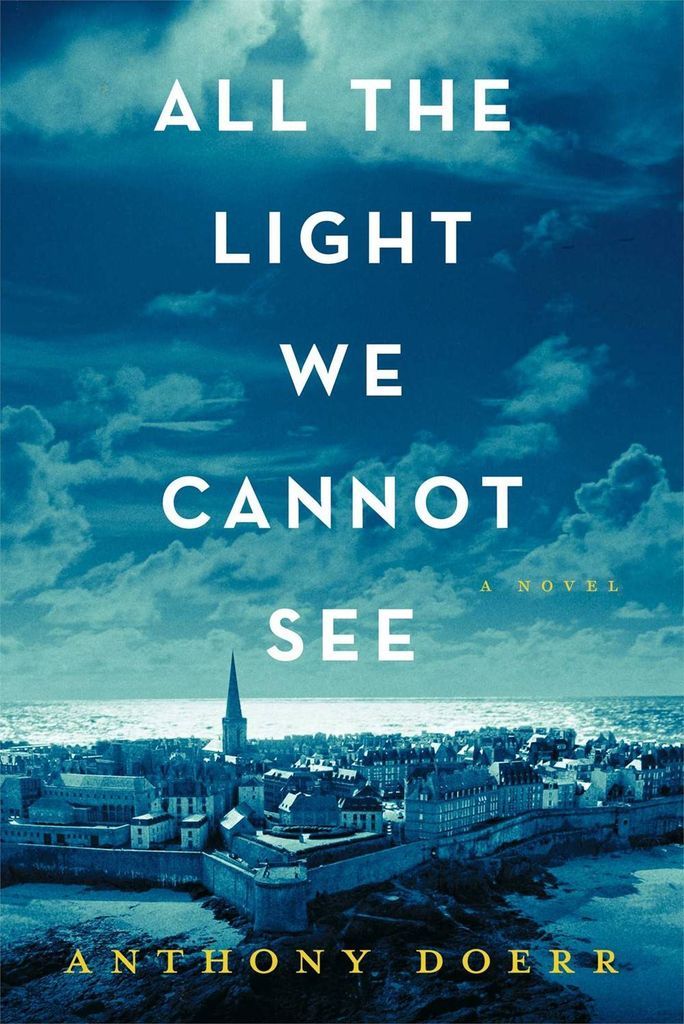

“Marie-Laure counts the chapters that remain. Nine. She is tempted to read on, but they are voyaging on the Nautilus together, she and Etienne, and as soon as he returns, they will resume. Any moment now.”

Any moment now. I kept thinking about that. My son will return, soon, September, a specific moment, but I wish it were any moment.

He’s been home once, from his duties in the Peace Corps, but it was a not an easy visit. It was last December, an emergency trip home to be with his father, who was critically ill with a malignant renal tumor. A big one. We learned of the diagnosis on a Thursday, then phone conversations, with doctors, government officials, airline representatives all day Friday, a plane ticket purchased on Saturday, and Eli to be home on Monday, little brother Seth already home on Christmas break from college.

The next few weeks were a jumble. We mostly tag-teamed the hospital vigils. Someone was always napping at the house, someone cooking, someone shopping. I trekked to the airport eight times in three weeks and made countless trips to the hospital. It was fraught and anxious waiting filled, surprisingly, with laughter. And despite the chaos we managed a Christmas dinner and a birthday celebration for Eli.

Cancer hadn’t been on the agenda, obviously, but neither had a visit from the E-man. Orchestrating not one but two holidays for my sons was a challenge. Of course, even normal life, without holidays, when everything is not normal, is a challenge. Eli’s Christmas and birthday packages crossed paths with him in the air, on their way to his post in the Philippines, so we improvised. One day my younger son, Seth, whispered to me, “I don’t have anything for Eli, so I’m just going to give him one of Dad’s presents.” I chuckled when his father later confided the same, “I don’t have anything for Eli, so I’m going to give him a shirt I got for Seth.”

The next day Eli said to me, “For your Christmas present I was going to record myself reading from Wind in the Willows, but I ran out of time. Now I can read it to you in person.” It is an old Christmas tradition for us, and I was moved when, in the midst of all the bustle and stress, he remembered it.

My favorite chapter is Dolce Domum, sweet home. That’s the one, you’ll remember, when Mole and Ratty are in the wood, and Mole finds his old home, the place he had abandoned when he threw down his paintbrush with a “Bother!” — obeying the imperious call of springtime, of “up above.” For years now, on Christmas, the boys have appeased me, letting me read that chapter aloud.

The human voice is my favorite instrument, and reading aloud is important in ways that I can hardly express. Ordinary and ancient magic: breath and sound and time, weaving a narrative. And whether it’s a story of return, Mole to his home, or a story of grand adventure, Marie-Laure and her Uncle Etienne with Jules Verne on the Nautilus, to begin aloud together, especially a longer work, always involves both risk and promise—the risk of interruption, broken narrative, and the promise that the reading will always be shared, requiring patience and fidelity, when, like Marie-Laure, we are tempted to read on alone.

Merely having my sons home was enough. But this gesture, Eli’s desire to read that chapter, knowing what a comfort those lines are, “caressing appeals… invisible little hands pulling and tugging, all one way!” toward home—this was a kindness, and no gift could have been more dear.

But in the confusion, we didn’t have a chance to read together. Next year.

On Christmas day, we learned that my ex-husband’s prognosis was excellent, the surgery successful. And that was the loveliest possible gift for those three men, father and sons.

On the way to the airport to drop off Eli for his return to the Peace Corps, I made a suggestion.

“Hey, fellas. I have an idea.”

“What?”

“Next Christmas, let’s not do cancer.”

“Okay.” Gentle laughter. “Good plan.”

Any moment now!

“They are voyaging… together, and as soon as he returns, they will resume.”