On Sharing Books When You’re a Margin Scribbler

This is a guest post from Mariam Tareen. Mariam is a writer and editor from Lahore, Pakistan. She has an MA in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway, University of London. She loves books, and would love to write one some day. Follow her on Twitter @mariamtee.

____________________

No! You can’t write in a book. You’re destroying it! Use bookmarks, don’t fold corners!

Okay, no one’s ever been quite that dramatic but there’s a general feeling among diehard book lovers that books are sacred objects and that they should remain pristine. Many dedicated readers feel this way, including my husband.

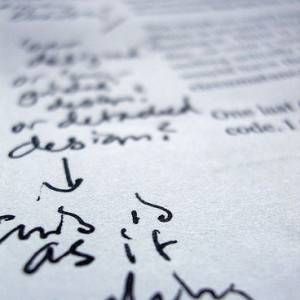

My husband and I are both avid readers, and we consider an evening spent reading an evening well spent (except when Netflix gets in the way.) But we differ in how we treat our books. When I read, it is with a pencil in my hand. I like to write in the margins of my books – my reactions, connections to other things I’ve read – rarely profound, my scribblings can be as nonsensical as a “wow!” or “super interesting” underlined three times.

My husband, on the other hand, doesn’t even fold a corner of a page to mark where he stopped reading. He uses makeshift bookmarks, a receipt, a folded piece of paper. When I showed him my copy of Anna Karenina, with its front page torn off, the spine badly wrinkled, and its pages withered from having survived a tumble into the pond in Kensington Gardens in London, he was horrified.

This big difference in our personalities proved not to be a deal breaker. We married, and things seem to be going okay. The people we choose to spend our lives with don’t need to be identical to us. No, I have no problem with our differences. The problem is, what happens to the books we share?

I have never shared books with anyone. Ever since I’ve been old enough to own my own. My books are more than the stories within them. My collection of books is my history. Each has a date when I finished reading, a heart if I loved the book, on the last page. Each book reminds me of a specific time in my life, and of the specific person I was then.

Now I can ask a lot of my husband, but I can’t expect him to read a book that is filled with my random words and underlining. I wouldn’t want to read a book filled with another person’s marginalia (unless I wanted to know more about that person). But this creates a problem for when we both want to read the same book. The more I love a book, the more I want to share it with him, but the problem is that the more I love a book, the more heavily marked it is. What was I to do then, give up my scribbling? Just read, and fight the urge to write back? Not possible. When the time came, and when I wanted him to read a book I had read and loved, I didn’t give him my copy. I bought him a new one.

I get it, reading a book is about the words. The story. The feelings it invoked. The ways in which the book expands our intellect. But if a book is only meant to be read, that implies a one-way movement of knowledge from the page to my mind. What if I want to engage with the book? To “talk back to it” as George Steiner has said?

Writing in the margins of a book leads also to a more informed second reading, both of the content of the book, and of ourselves. My copy of Anna Karenina reminds me of my first reading of this magnificent novel. The first time I read anything by Leo Tolstoy. It reminds me of the awe that his words inspired, and how much more strongly I wanted to be a writer. It reminds me of the time I spent in London when I was reading it, taking my time, letting months go by, walking to a quiet coffee shop every evening with the mammoth object and settling in to read it by the window over a piping hot Americano. Books have meaning as objects, and writing in them is an act of ownership over that object, an attempt to make it personal, intimate.

Writing in a book transforms a one-in-a-million object into something unique, irreplaceable. Writing in a book makes it ours. Our bookshelf becomes a kind of personal history, an autobiography, the scribblings inside books become an informal journal.

Physical books can also be passed on. Just a couple of years ago, a first edition of The Great Gatsby was sold for $112,500 at Sotheby’s. It had been owned by writer and critic Malcom Cowley, who had studied Fitzgerald’s personal annotated copy of the novel and copied over 100 notes into his own copy. According to Richard Austin, head of the auction house’s books and manuscripts department, without the annotations, the book would have sold for 30 percent less.

I have no illusions of grandeur there and don’t expect my annotated books to be sold at auction for thousands of dollars. However, I’d like to think that one day, my books will pass on to my children, and that when they read one of my books, they can see how I read it.