SUPERCUT: George Saunders

SUPERCUT is a new feature where we collect interesting snippets from the best author interviews and combine them into a single post.

Here’s a selection of the best and most interesting from Saunders’ recent interviews.

From The Guardian

(On his “pared down, thrillingly compact” style): “The thing I found was if you want to avoid creating a world that looks habituated, compression is a great way to do it. Because we’re habituated, both in life and in fiction, to certain ways of expressing things. So – if someone asks how do you get to the hospital? The answer is four blocks and turn left. But the actual experience of going to the hospital is a thousand pointillistic things that are probably sub-articulable. And then: what are the linguistic corollaries that I can make, that actually come alive anew?”

(The full article is here.)

From The New Yorker

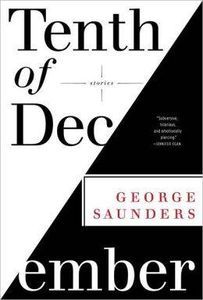

(After publication of his story “The Semplica-Girl Diaries” in the Oct. 15, 2012 issue. That story is included in Tenth of December.)

Interviewer: Where did the word “Semplica” come from? Does it have some special meaning for you?

Saunders: That was what they were called in the dream. I think I woke up knowing that. There’s nothing symbolic or secret about it. And I somehow knew from the beginning that “Semplica” was the name of the guy who had “pioneered this innovative technology.”

One thing I always feel in the midst of trying to talk coherently about a story I’ve finished is that, you know, ninety per cent of it was intuitive, done at-speed, for reasons I can’t quite articulate, except in the “A felt better than B” way. All these choices add up, and make the surface of the story, and, of course, the thematics and all that — but I’m not usually thinking about any of that too much, or too overtly. It’s more feeling than thinking — or a combination of the two, with feeling being in charge, and thinking sort of running around behind, making overly literal suggestions, and those feelings being sounded out and exercised and manifested via heavy editing and rewriting (as opposed to, say, planning and deciding). The important part of the writing process, for me, is trying to make choices that push the story in the most interesting direction, by which I mean the direction that causes the story to give off the most light. The story’s goal is to be fascinating and stimulating and irreducible; the writer’s job is to micromanage the text to make this happen.

(Read the full interview here.)

From The Slate Book Review

Andy Ward (Saunders’ long-time editor): A lot of people say to me, “God, it must be so fun to work with George Saunders. Do you even have to edit him at all?” And they say it like they assume you shun all editing, or don’t allow editing, which is always really funny to me, because you are a person who craves feedback, who wants to be pushed and challenged and sent off in new directions. This all sounds self-serving, I realize, so I should add: Of course, at this stage, you don’t need an editor. But you want an editor. Why?

Saunders: No, I definitely need and enjoy having an editor, and for the exact reasons you state. There’s a really nice moment in the life of a piece of writing where the writer starts to get a feeling of it outgrowing him—or he starts to see it having a life of its own that doesn’t have anything to do with his ego or his desire to “be a good writer.” It’s almost like an animal starts to appear in the stone and then it starts to move, and you, the writer, are rooting for it so hard—but may not be able to see everything clearly after working on that stone for so long.

(You can read the full text of this fascinating exchange here.)

From Time Out Chicago

(Saunders grew up in the Chicago suburb Oak Forest.)

Interviewer: The characters in Tenth (of December) often face some sort of moral or ethical dilemma—personal shortcomings or literally rescuing someone’s life. Consequently, there are subtle religious references throughout. Is religion something that was part of your life?

Saunders: Yeah, as a kid I was a real strong Catholic. Once you have that when you’re young, it makes a space in your heart. Our minds, our perceptual apparatuses as they come from the factory, are inefficient to cope with or perceive the bigger thing. So you turn to whatever you turn to, but the notion of, “Whatever my senses tell me, that’s all I have to tell.” That seems, like, totally crazy.

(Read the full interview here.)