Booze Your Way Through the Holidays Hemingway Style

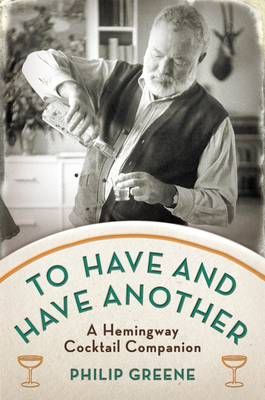

This is a guest post from Philip Greene. He is one of the founders of the Museum of the American Cocktail (New Orleans), and is the author of the newly released book To Have And Have Another – A Hemingway Cocktail Companion, a drinker’s guide to the life and works of Ernest Hemingway. It’s a critically-acclaimed collection of 55 authentic recipes, all tied to his prose, letters, biographies, and his adventures around the world, chock full of excerpts, drink histories, colorful anecdotes, and vintage photos and ads. It’s on the Holiday gift guides of the Wall Street Journal, Imbibe, Wine Enthusiast, Food & Wine, and many many other publications. Philip is the Trademark Counsel for the U.S. Marine Corps, based at the Pentagon, and he lives in Washington, DC with his wife and three daughters. Follow him on Twitter @philipgreene.

_________________________

Photo from Pamplona café in 1925 showing Hemingway, Harold Loeb (background), Lady Duff Twysden, Hadley, and Pat Guthrie. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, JFK Presidential Library, Boston

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) was to many the prototype for The World’s Most Interesting Man. Wounded in World War I, Paris of the Lost Generation 1920s, running with the bulls in Pamplona, hunting big game in Africa, trophy fish in the Gulf Stream, boxing matches in Bimini, covering (and fighting in) the Spanish Civil War and World War II, you name it. He went just about everywhere and did just about everything. And through all of his adventures and travels, he picked up a lot of good dope about drinks. He liked his whisky neat, or with a bit of lime; he liked his Martinis bone dry and damned cold. He didn’t much go for sugary drinks, and he didn’t suffer fools. Did I say he knew about drinks?

A man for all seasons, he didn’t just know the warmer climes of Spain, Key West and Cuba. He paid his dues in Paris, Austria, Northern Italy, the mountains of Idaho, and “up in Michigan,” so he knew cold weather. So as we all careen into another winter season, into the belly of the Holidays, here are a few drinks that Papa enjoyed in frostier times.

Hot Rum Punch

1 ½ 750 ml bottles Barbados or lighter Jamaican Rum

1 750 ml bottle Cognac

3 quarts boiling water

2 cups lemon juice

Brown sugar, to taste

Handful of cloves

Add all ingredients to a sturdy stockpot or crock pot, stir occasionally. Garnish each cup with a spiral of yellow lemon peel, careful to remove the white pith, as it contains unwanted bitterness.

(Oxford University Hot Rum Punch, from Hem’s friend Charles Baker, Jr., from The Gentleman’s Companion, Part II.)

Hemingway and Hadley, 1922. Nice day for a hot rum punch. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, JFK Presidential Library, Boston

Hemingway and his young bride Hadley moved to Paris when he was just 22, and they embraced this drink that first winter of ‘21. From a letter to Sherwood Anderson:

“Well, here we are. And we sit outside the Dome Café, opposite the Rotonde that’s being redecorated, warmed up against one of those charcoal brazziers [sic] and it’s so damned cold outside and the brazier makes it so warm and we drink rum punch, hot, and the rhum enters into us like the Holy Spirit.”

If punch is too much fuss, a nice tot of rum can warm the soul, too. From A Moveable Feast, Hem tells of a blustery day spent writing in a clean, well-lighted place:

It was a pleasant café, warm and clean and friendly, and I hung up my old waterproof on the coat rack to dry and put my worn and weathered felt hat on the rack above the bench and ordered a café au lait. The waiter brought it and I took out a notebook from the pocket of the coat and a pencil and started to write. I was writing about up in Michigan and since it was a wild, cold, blowing day it was that sort of day in the story. I had already seen the end of fall come through boyhood, youth and young manhood, and in one place you could write about it better than in another. That was called transplanting yourself, I thought, and it could be as necessary with people as with other sorts of growing things. But in the story the boys were drinking and this made me thirsty and I ordered a rum St. James. This tasted wonderful on the cold day and I kept on writing, feeling very well and feeling the good Martinique rum warm me all through my body and my spirit.

Bloody Mary (makes one pitcher)

16 oz vodka

16 oz tomato juice

1 tablespoon Worcestershire sauce (or A1)

1 ½ oz fresh lime juice

Celery salt (to taste)

Cayenne pepper (to taste)

Black pepper (to taste)

A hale and hearty Hemingway, sent from Gstaad, Switzerland to Scribner’s in February, 1927. The note on the back read, “This is to re-assure you if you hear reports of another of your authors dying of drink.” Meanwhile, on a skiing holiday in Schruns, Austria, the locals called him “the Black Kirsch-drinking Christ.” Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, JFK Presidential Library, Boston

On Christmas morning, nothing hits the spot like a good Bloody Mary. Hemingway took great pride in his recipe, as this 1947 letter to his friend Bernard Peyton shows:

“To make a pitcher of Bloody Marys (any smaller amount is worthless) take a good sized pitcher and put in it as big a lump of ice as it will hold. (This is to prevent too rapid melting and watering of our product.) Mix a pint of good russian vodka and an equal amount of chilled tomato juice. Add a table spoon full of Worcester Sauce. Lea and Perrins is usual but can use A1 or any good beef-steak sauce. Stirr. (sic) Then add a jigger of fresh squeezed lime juice. Stirr. Then add small amounts of celery salt, cayenne pepper, black pepper. Keep on stirring and taste it to see how it is doing. If you get it too powerful weaken with more tomato juice. If it lacks authority add more vodka. Some people like more lime than others. For combatting a really terrific hangover increase the amount of Worcester sauce – but don’t lose the lovely color. Keep drinking it yourself to see how it is doing. I introduced this drink to Hong Kong in 1941 and believe it did more than any other single factor except perhaps the Japanese Army to precipitate the fall of that Crown Colony. After you get the hang of it you can mix it so it will taste as though it had absolutely no alcohol of any kind in it and a glass of it will still have as much kick as a really good big martini. Whole trick is to keep it very cold and not let the ice water it down.

Glühwein

1 quart dry wine

Peel of one lemon and 1 orange

Spices to taste

1 tablespoon sugar

“If ground spices are used, cook 1 to 2 teaspoonfuls of them with the lemon and orange peels and sugar in 1 cup water until flavor is well dissolved and then add the wine. It is even better to use 1 crushed, but not grated, nutmeg, 2 to 3 inches stick cinnamon, and a half dozen whole cloves; boil them with sugar and lemon and orange peels in the wine and strain out. Do not allow the wine to boil as this detracts from the flavor.”

(Recipe from David Embury’s The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks)

Glühwein is a mulled, spiced wine popular in German-speaking countries. The term literally means glowing wine in German. It’s featured in A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway’s tale of ambulance corps officer Frederic Henry and nurse Catherine Barkley, set in Italy during World War I. The two lovers make their escape from the war, into Switzerland. They “lived in a brown wooden house in the pine trees on the side of the mountain and at night there was frost so that there was a thin ice over the water in the two pitchers on the dresser in the morning.” Soon the snows came, and they spent much of their time indoors. By the middle of January, Frederic has grown a beard, and “the winter had settled into bright cold days and hard cold nights.” They went for walks along snow-packed roads, Catherine wearing hobnailed boots and a cape. On one of these walks they stopped off for a rest:

There was an inn in the trees at the Bains de l’Alliaz where the woodcutters stopped to drink, and we sat inside warmed by the stove and drank hot red wine with spices and lemon in it. They called it glühwein and it was a good thing to warm you and to celebrate with. The inn was dark and smoky inside and afterward when you went out the cold air came sharply into your lungs and numbed the edge of your nose as you inhaled. We looked back at the inn with light coming from the windows and the woodcutters’ horses stamping and jerking their heads outside to keep warm. There was frost on the hairs of their muzzles and their breathing made plumes of frost in the air. Going up the road toward home the road was smooth and slippery for a while and the ice orange from the horses until the wood-hauling track turned off. Then the road was clean-packed snow and led through the woods, and twice coming home in the evening, we saw foxes. It was a fine country and every time that we went out it was fun.