A Conversation with Book Sculptor Brian Dettmer

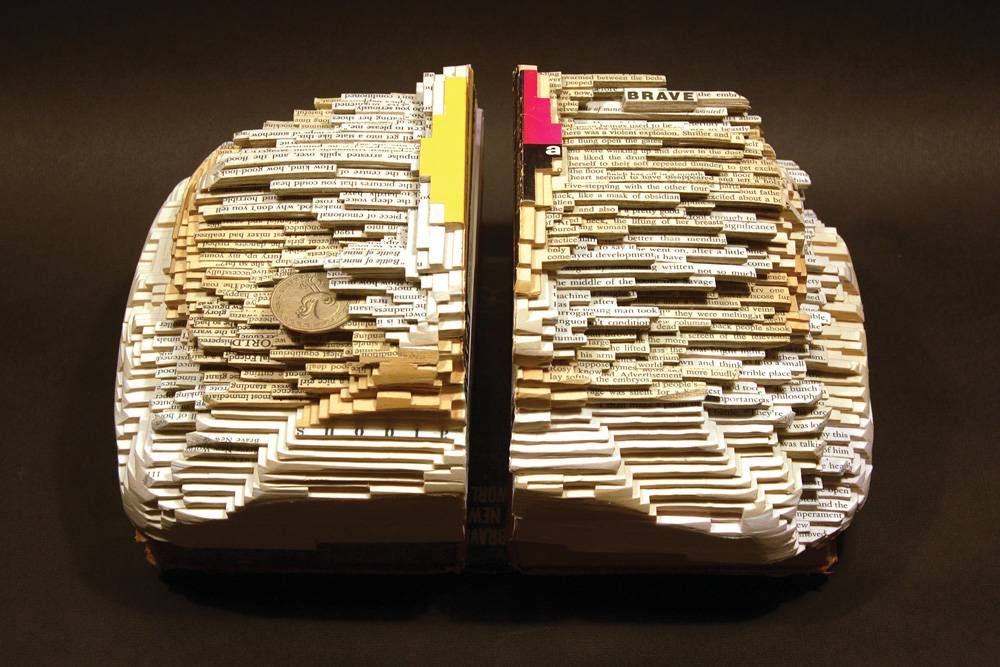

Artist Brian Dettmer approaches books with knives, tweezers, and blade-sharp ideas about the meanings of media and information. For over ten years, he has carved and reshaped old, used books, revealing new connections by slicing away segments of pages.

In his Atlanta studio, Dettmer transforms medical texts, art history tomes, military manuals, and more. It’s a painstaking process: He seals a book, then cuts into it from the front and works through it a page at a time. Sometimes he combines books into towers, blocks, or whorls. Other works use single books, their layers turned into teeming, intricate visions. Dettmer only cuts away fragments of paper, rather than reordering or replacing them.

New Books of Knowledge, 2009, Encyclopedia Set, Acrylic Varnish, 16″ x 26-1/2″ x 10″Image Courtesy of the Artist and Packer Schopf

New Books of Knowledge, 2009, Encyclopedia Set, Acrylic Varnish, 16″ x 26-1/2″ x 10″Image Courtesy of the Artist and Packer Schopf

The sculptures are beautiful objects in and of themselves, but you also find yourself drawn into the books’ original subjects. A cartographic work, for instance, might make you reconsider America’s nets of roads, dream up your own highway narrative.

Dettmer has several solo shows this year, including one this fall at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia. He speaks with Book Riot about his work—and gives us a preview of his latest projects.

____________________________

JP: Please walk me through your work process. How do you select books to carve? Do you skim or read them first? I was struck by your description of “reading with my knife.” By the time you start cutting into a given book, do you have a certain image in your mind’s eye, or does this “reading” process guide the outcome, layer by layer?

BD: When I’m looking for a book to work with, the size, title, subject, content and overall feeling of the book all play a big factor in the work. I will skim through a book to make sure the illustration quality, design, and even paper type will work but other than that I try not to know the book too well before I begin because I want chance to play a large role.

I might have an idea of an overall feeling because of the book’s style or I might set up a set of rules or guidelines to direct the outcome in a certain direction but I never plan a specific page or image before I begin. It’s exciting because it unfolds while I’m diving into it, just like a good book should.

JP: In your recent work, you’ve focused more on text than image. What kinds of books do you choose with this in mind? How do the words you find while carving shape the process and outcome?

BD: When I’m working with a reference or non-fiction book it’s interesting to isolate a fragment of text and see how it operates. The meaning can shift in a new direction, open up to a number of possibilities, or point to a hidden truth in the text. Language can function like an image and an image can incite a phrase or association that may be indelibly tied to language. The recent language-based works have allowed me to explore fiction, specifically paperback books. I like the idea of connecting several books of a similar genre or subject to work on so it’s usually still an approach to a general idea of a subject rather than the specific text of a single author.

JP: Your work results in all sorts of new and fascinating juxtapositions, contrasts, and confluences. Are there one or two standout moments you could share, when the images or text you uncovered connected in a particularly powerful and unexpected way?

BD: This happens hundreds or thousands of times each day while I’m working. I think it’s most exciting when I see a pattern or echo in elements or structures that I had never thought to see in the same context, like when a scientific drawing of a cell becomes juxtaposed with the map of a city park or a pattern on an afghan carpet relates to an organizational chart showing U.S. imports in the mid-century.

New Books of Knowledge, 2009, Encyclopedia Set, Acrylic Varnish, 16″ x 26-1/2″ x 10″Image Courtesy of the Artist and Packer Schopf

New Books of Knowledge, 2009, Encyclopedia Set, Acrylic Varnish, 16″ x 26-1/2″ x 10″Image Courtesy of the Artist and Packer Schopf

JP: When you first started carving books, did you have any moments of hesitation about slicing up a book? Did you have to get over habits of not damaging books and did those first cuts feel transgressive? Or did you easily see them as an artistic medium, ready to be put to use?

BD: Yes, I began as a painter, exploring codes and language systems and playing with the dichotomy between the physicality of language and the ideas it can represent. This lead to a series of collages I was working on in which I would rip up newspapers and then eventually books, and applying the fragmented pages to the surface of the canvas. It was around 2000. I was feeling very guilty about ripping up books even though I knew the books I was using were mass produced and we were at the beginning of a shift in the way we absorb information. I knew I had to make the work worth it. This is what lead to looking at books as a specific material and subject to focus on and explore.

My first works were with telephone books and other disposable catalogs and I slowly developed a tolerance. Now, I don’t feel guilty as long as I know I’m working with something that is not rare and more often than not, has completely lost its function, but I do still feel an obligation to the material, to respect it and push it in a worthy direction to raise these questions in the viewer.

JP: You’ve used everything from medical texts and encyclopedias to paperbacks for your artworks. Are there any kinds of books that you have yet to try, that you’re hoping to sculpt?

BD: Right now I’m working on a series of small alterations from book pages of U.S. state flags. I like the idea of doing the minimum intervention to get the maximum message. Each page will be cut and folded to become something new. There will be visible clues and ties to the original print. They will be small prototypes for sculptures that would be illegal if I did them with real flags. It’s about the freedom of speech issues that come from dissent and the odd idiosyncrasies that come from state laws and local cultures.

New Books of Knowledge, 2009, Encyclopedia Set, Acrylic Varnish, 16″ x 26-1/2″ x 10″Image Courtesy of the Artist and Packer Schopf

New Books of Knowledge, 2009, Encyclopedia Set, Acrylic Varnish, 16″ x 26-1/2″ x 10″Image Courtesy of the Artist and Packer Schopf

JP: How has your working/artistic relationship with physical books changed in your reading life? Do you find that your personal reading habits change, either in what you read or what form you read it in?

BD: I listen to a lot of audiobooks because I have more listening time than viewing time since I’m constantly working in the studio. So, I can hear a book while working on another. I read a lot when I travel and I still prefer traditional books. I haven’t adapted to the e-readers and I find it tough to read more than a few pages online even through that’s how I get most of my information now.

JP: With the news that the Encyclopedia Britannica will stop publishing a print version, have you been mulling over a possible Britannica project?

BD: I have worked with Britannica before, in fact the piece I’m currently working on is from a Britannica set from the 1960s. I began this piece two months ago so it’s a coincidence given this recent news. It is very sad. I knew the day would come but I didn’t think it would be so soon and I couldn’t believe that only 8,000 copies of the 2010 edition had been sold. I think I need to get one just to have it fifty years from now.

I could write pages on this and I know it will lead to a series of projects. I think it is important to ask if people will be able to go online to see how thoughts, beliefs and ideas have changed over the years. It’s nice to find an old encyclopedia to see how things have changed and that won’t be possible with an internet that is constantly erasing itself as new information replaces the old. Plus, we are now relying on a constant flow of cheap energy to maintain our information. Let’s hope we can continue this.

____________________________

Image Credits:

New Books of Knowledge, 2009, Encyclopedia Set, Acrylic Varnish, 16″ x 26-1/2″ x 10″

Image Courtesy of the Artist and Packer Schopf