2012 Tournament of Books: The Odds

Just a coupla days until the 2012 Tournament of Books gets underway. I’ve narrowly completed my reading of the field and am ready to present you with a full handicapping of the contenders.

Here we go…in alphabetical order by title.

A debut novel has never won The Rooster, but this year two debuts have excellent shots. The Art of Fielding is one of them (The Tiger’s Wife is the other). This is nominally a baseball book, but really it’s more of a campus novel with a Melville fetish. The book has several strong characters and some quite compelling prose, but there are three serious weaknesses. First, the ending is a mess (Rooster winners tend to have very good endings). Second, the scope is small (Rooster winners tend to have more range). Third, it’s pretty dang conventional (Rooster winners tend to do something a little different). In the end, The Art of Fielding is a fine literary debut. This will both let it advance and prevent it from winning. (Judging note: Fielding’s first round match-up is against Open City and judged by Jay Kaspan Kang, a writer for the sports-themed website Grantland. Make note of that).

Odds of winning: 12-1

Somehow, this one slipped largely under the radar in 2011. It’s a damn shame. Ondaatje describes the transatlantic voyage of three adolescent boys aboard a steamship in glorious, exacting prose. This is a novel of memory and of melancholy, as the grown narrator recounts his most vivid childhood experience. The scene and sensory world of the ship and its passengers is enveloping. But, again we have the trouble of the ending set in the contemporary, which suffers when compared to the vividness of the ship. The novel mimics this boy’s experience; a shimmering beginning makes what comes after seem a fallen and colorless world.

Odds of winning: 32-1

This is a brutal book. Pollack creates a McCarthian world of ambient violence and hard-cases, except that even the wisp of empathy present in The Road or No Country for Old Men is extinguished. For those who get a thrill out of horror and untempered violence, I’m sure this is knock-out. I could barely finish it, and I would be surprised if it does much here.

Odds of winning: 25-1

I kept thinking of one of last year’s contenders, Bad Marie, while reading Green Girl. Like Marie, Ruth, the protagonist, is a green girl, the aimless, deadly attractive, searching, hunted, watched, and narcissistic object of desire. Told in a series of epigraphs, Green Girl charts Ruth’s disaffection, from America and an abusive boyfriend, to a purgatorial London of indecision, memory, and objectless yearning. The novel is as disjointed and precarious as Ruth herself, always on the verge of falling (or being ripped) apart. As a reading experience, this lingered. As a work that three or more judges will prefer to more coherent, comprehensible novels, I have my doubts. Still, I’m glad to have read this one (as I think fans of Play It As It Lays or The Bell Jar will be. This stands firmly in the tradition of those novels).

Odds of winning: 16-1

There are a few excellent short novels here this year. And none of them are likely to do much here (maybe Salvage the Bones. More on that in a bit). The Last Brother is set in Mauritius during World War II, where a ship of Jewish refugees is stuck when their documents come under investigation. A young local boy, himself the object of no small domestic turmoil, befriends one of the interned Jews. Spoiler alert: I wish I could say it ends well. I found myself conflicted about The Last Brother; I had the strong feeling of being manipulated, but I was all right with that. The core of this novel is the desire to have a friend. A confidant. Someone with whom to stand against an uncaring world. And maybe it’s because I have brother, or maybe it’s because I have a young son, but the story of two boys clinging to each other meant something to me.

But, like The Sense of an Ending or Salvage the Bones, The Last Brother is probably too small to win. That doesn’t mean it or the others aren’t good, just that when it comes time to hand out the hardware, depth and density tend to beat concision and focus.

Odds of winning: 16-1

Lightning Rods manages to satirize two oppressive institutions at once: corporate America and the male gaze. Joe, our upbeat, enterprising protagonist, has an idea: what if the ambient sexual tension of the office could be defused by having glory holes available to focus and alleviate male sexual desire? Would this increase productivity? Would it be cost-effective? What kind of woman would sign-up…and what should they be paid? Like Baker’s House of Holes or Perotta’s The Leftovers from 2011, Dewitt takes an absurd premise and plays it out. And it is indeed a wry and wrecking novel, though Joe’s ingenuousness strains our suspension of disbelief even more than his million dollar idea. Lighting Rods suffers the fate of most satires—the appeal to the mind ultimately prevents an appeal to where the heart resides. (Note: a comic novel has never won The Rooster.)

Odds of winning: 12-1

If you are reading this, you already know about The Marriage Plot. Here are a few observations for handicapping purposes. One, it’s such a small novel, in terms of scope. It’s really about a love triangle of book nerds (and the most annoying kind of book nerd–the kind who like to talk about theory. Voluntarily). Two, I think Madeline’s character is a problem for the novel’s chances here. After her long opening sections, she fades into the scenery, an object of the novel rather than one of its subjects. Three, we read and have read so many coming-of age-novels that it takes a lot to delight us (like, say Skippy Dies did last year). Erudition and ambiguous representations of literary celebrities aren’t enough to spark our passion.

Odds of winning: 16-1

A personal favorite, Open City is elliptical and poetic. It is a novel of exploring turned wandering turned wondering. Julius, the narrator, is finishing a fellowship at Columbia when he starts a series of perambulations through New York. Open City becomes a diary, an urban field guide, and a commonplace book of the city itself. Julius is both urbane and urban, a multiracial, postcolonial polymath, who takes on a tour of a place we have been, but still don’t quite know. It is wonderful. And it won’t get far. Just as Green Girl lacks cohesion and The Cat’s Table lacks satisfying closure, Open City lacks, well, a plot. This isn’t a book about what happens, it is a book about what is. It’s going to frustrate some, I think, but it hit me square.

Odds of winning: 8-1

Salvage the Bones haunted my readings of the other debut novels in the field (save Open City, which is much less plot-driven than the others). Ward takes us to a place we know and shows it to us as we know it must be. Southern poverty isn’t dressed up with fabulism, and intra-family tension isn’t allegorized with tigers. It’s short, giving us just enough of this black family’s life to understand that it is tough and precarious. And then Katrina comes. (List idea: great literary floods. Noah, natch. The river in As I Lay Dying. Another Louisiana flood in Coming Through Slaughter. The end of Their Eyes Were Watching God. Others?). I think of Salvage the Bones as less of a novel and more of an extended set-piece; without some story of what happens to these characters after the hurricane, the novel feels incomplete, like a sub-plot or fragment of a larger work. (Here’s the order in which I am most excited for the next book by the debut authors here: Ward, Cole, Obreht, Russell, Harbach.)

Odds of winning:16-1

The Sense of an Ending has some structural similarities with The Cat’s Table; it is a kind of memory play of an older man reminiscing about a more vibrant time of his life. It is also neater than The Cat’s Table, with a short story’s focus and payoff. Still, at its best, The Cat’s Table is better than The Sense of an Ending is at its best (though also perhaps worse at its worst). I prefer fascinating messiness to admirable cleanness, though I think I might be in the minority of the literarily inclined in that regard. Neither of these has a real chance to go far, but they are illuminating case studies.

Odds of winning: 16-1

Tough first round match-up against State of Wonder, but judged by uber-geek Wil Wheaton. Hmmm. The Sisters Brothers is a neo-Western dramedy that is violent, taut, and light-hearted in a way that will be familiar to True Grit fans. Like True Grit, the fun here is the erudite, grim, and ironic dialogue of these merciless men. Had The Sisters Brothers a more engaging plot like True Grit‘s, I would give it a puncher’s chance in the Tournament, but even if it does upset State of Wonder in round one, there are still quicker guns waiting in other dusty towns. (In fact, I would have installed State of Wonder at 3- or 2-1 if not for the judge/title pairing it got in the first round. A Sisters Brothers win would be an upset that everyone who pays attention saw coming.)

Odds of winning: 4-1

State of Wonder is the favorite for one reason: it is the best combination of plot and character in the field. You get these two things right, and baby you’ll go far. Marina Singh gives Patchett a compelling character with compelling work to do: journey into the heart of the Amazon river–and into her own past. Her topographical exploration maps in fascinating ways onto her psychological journey. Its artistic merits are enough reason to put State of Wonder in the pole position, but it also has a real-world advantage: it is the best selling of the books in the field and so is likely to be a zombie round winner, should it lose before the finals. In effect, this means that State of Wonder would have to lose twice to be kept out of the finals. Ain’t. Gonna. Happen.

Odds of winning: 8-1

I don’t know if it’s something about the make-up of the Tournament this year or if it’s just the way my mind works, but I keep finding pairs of books here. Swamplandia! seems to me a bizarro-version of The Tiger’s Wife. Both rely on, let’s call it “realist non-realism,” but where Obreht goes for solemnity, Russell goes for delight; where Obreht’s language is allusive and studied, Russell’s is inventive and playful. For all its creativity and exuberance, Swamplandia! is the story of a family, just as The Tiger’s Wife is. Both are great reads and both are exciting omens of what these young women can do. But neither really takes chances, neither has an edge that, as Kafka said, can break the frozen sea inside of us.

Odds of winning: 12-1

I’m not as versed in contemporary British literature as I should be, and even in graduate school, I learned about British literature more than I ever came to understand it. With that disclaimer in place, when I think of an English novel, The Stranger’s Child is what I am thinking of. Mannered. Beautiful. Repressed. Intricate. Enthralling. Claustrophobic. The sentences seem compressed and all the more radiant for it; their genesis is in rigid social constraint. I can intellectually recognize that this is a supremely accomplished novel, but I cannot love it. I don’t know if it’s my Americanness or my pathological desire to feel modern, but this seems like an anachronism, like a lovingly restored 1964 Mustang, brought up to date with today’s technology. (It also seems like a novel genetically-engineered for James Wood to review. And he reviewed the shit out of it in the New Yorker.) If the judges were all graduate students in British literature, this would be Michael Jordan. But they are not, so this isn’t.

Odds of winning: 8-1

Technically accomplished and lovingly imagined, The Tiger’s Wife does what it does better than any of the other books in this year’s field do what they do. Problem is, what it does is less ambitious that what some of the other books do. The central realm in Obreht’s novel is a place of fables and myths. It is framed, for reasons I am still working out for myself, by an un-urgent family narrative of considerably less interest. In a field of flawed but interesting novels, I think this elegantly executed novel will really stand out. In the final analysis, I put my chips elsewhere, but I expect The Tiger’s Wife to do well.

Odds of winning: 24-1

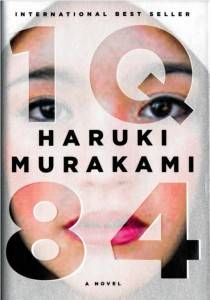

With all of the short novels in the bracket, 1Q84 feels like a leviathan. Let’s make one thing clear: a 900-page novel isn’t going to win. No shot. But if one of the things we love about art is that it offers us something we couldn’t ever imagine ourselves, 1Q84 delivers. Of the names here, Murakami is the most likely to be discussed in 50 years, and 1Q84 may well be his Gravity’s Rainbow–the signal work that repels as much as it attracts.