Making Moms Everywhere Blush: 1950s Teen Pulp Comic Magazines

There’s a common belief that we’re in an era of oversexualization of teenagers. Their media is packed with sexual overtones and undertones, and they’re learning about “adult topics” much too young.

Not only is this dismissive of rampant purity culture, which exists on all sides of the U.S. political spectrum and along a wide range of faiths, but it overlooks a fascinating era of teen pop culture from a bygone generation. The early 1950s — when (white) teenagers themselves became a capitalist world’s dream by being seen as a wholly unique demographic, thanks to burgeoning wallets, leisure time, and access to transportation — introduced young readers to a whole new category of blush-worthy literature: the teen pulp magazine.

Designed like comics, teen pulp magazines included characters and story lines which followed those more commonly seen in the adult romance market. Recall this era in literature did not have a designated YA category; there were books published for this age range, but it had yet to be defined as such. The development of teen-appealing magazines with teen-saturated storylines, though, fit in with the wealth of teen magazines of the era, including Modern Teen, Seventeen, and others.

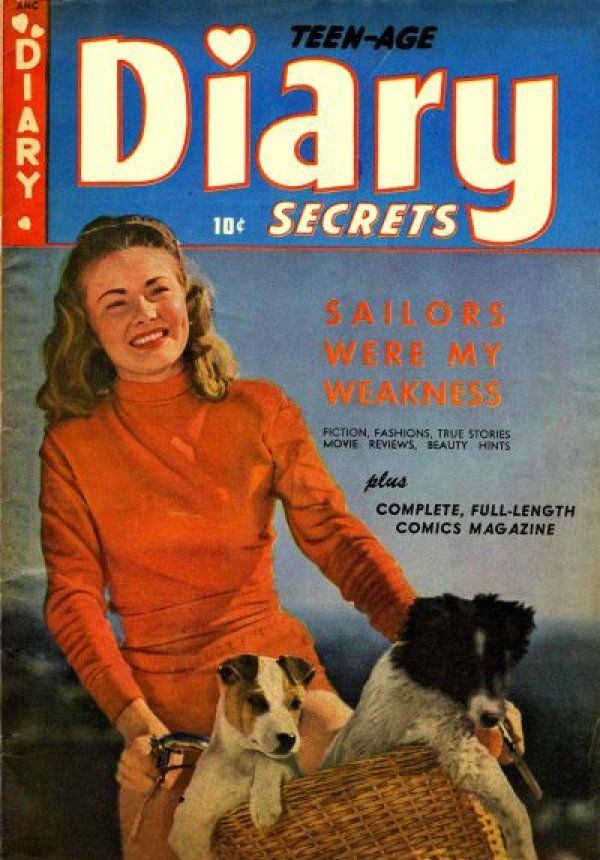

Teen-Age Diary Secrets launched in 1949 and ran for a little over a year. The comic magazine featured short stories of couples doing “adult” things and exploring “adult” topics. None of the teenagers look like teenagers, adding to the fantasies of those picking up the periodical. Though there were stand alone texts, the bulk of this magazine featured comic stories. Issue #4, for example, included “I Was Tired of Being Good,” a story of a girl who moves to a new town and reinvents herself to attract boys; “Sailors Were My Weakness,” about a girl thinking she’s being cheated on by a sailor; and “Breaking Hearts Was My Hobby!,” following a girl who, as you might guess, enjoys breaking boys hearts. All three were written by Dana Dutch and illustrated either by Chuck Miller or Matt Baker.

Teen-Age Diary Dream had a total of six issues, each costing readers a whopping 10¢. It was published by St. John, and issues 4 and 8 can be read online.

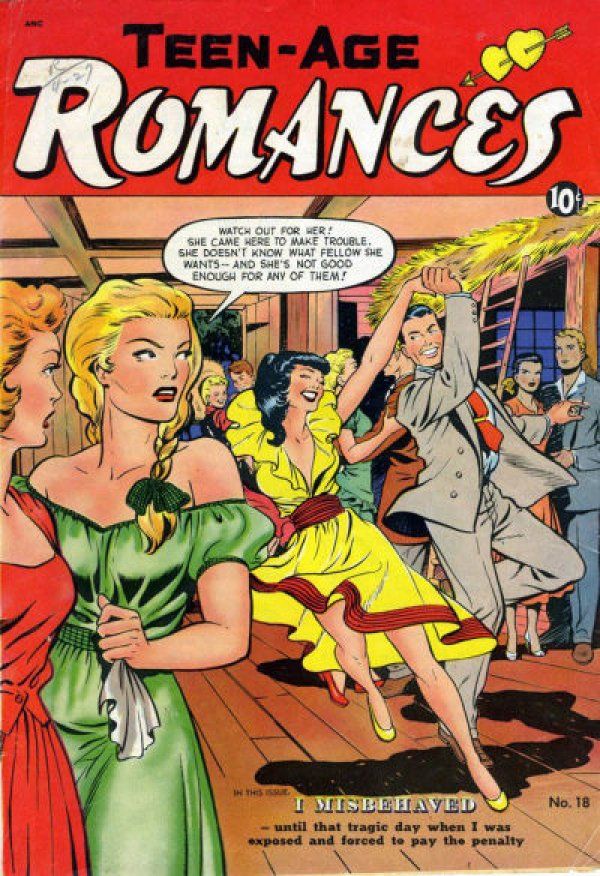

Teen-Age Romances followed a similar structure, and it was also published by St. John. Romances launched in January 1949 and had a longer life than Teen-Age Diary Dream, running 45 issues until it ended in 1955. Nearly every cover of the magazine included a comic cover, though a small set included photographic or painted ones.

The comic magazine included one-shot stories, beginning with three in each issue. It grew bigger as it found readership, and included not just romances, but powerful coming-of-age stories as well.

September 1949’s issue, titled “I Was A Hollywood Cinderella,” included stories like “Come-On Girl,” “My One Little Mistake,” and “Brushes to Beauty.” Many of the scripts were written again by Dana Dutch, with art from Matt Baker, Lily Renee, and others.

Full issues are available to read online.

St. John offered an assortment of other teen comic magazines, too, including titles like Teen-Age Temptations. It should come as little surprise what all of them have in common is a primarily white cast and primarily white target audience. When we think of the teen demographic emerging in this era, it is, of course, a white teen demographic.

Weddings were a major area of pop culture in the post-war era, and teen girls — the prime audience for these magazines — were enmeshed in the white wedding world. It’s easy to forget that even in the ’50s, the average age of a first marriage for middle class women was 19, meaning that many hours went into dreaming and planning for the big “I Do” and step into domesticity. Meghan M. McSweeney’s piece in the Journal of Americana offers a look at the ways and means by which wedding culture was sold to young women in this era.

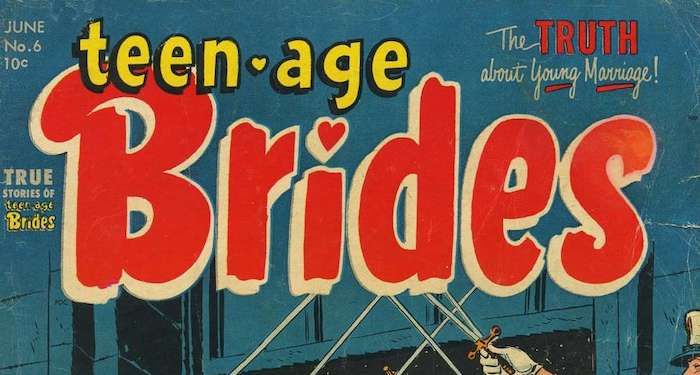

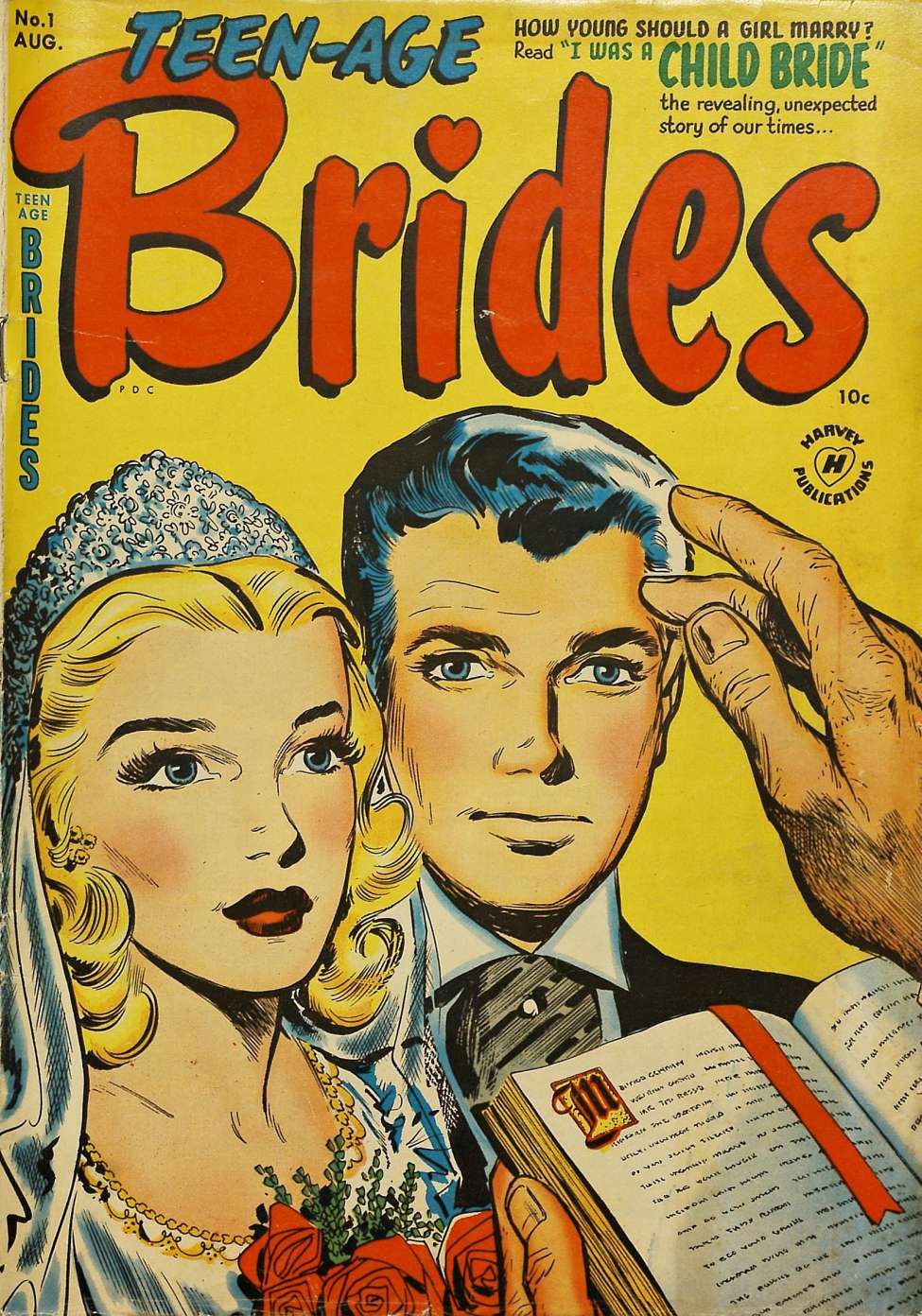

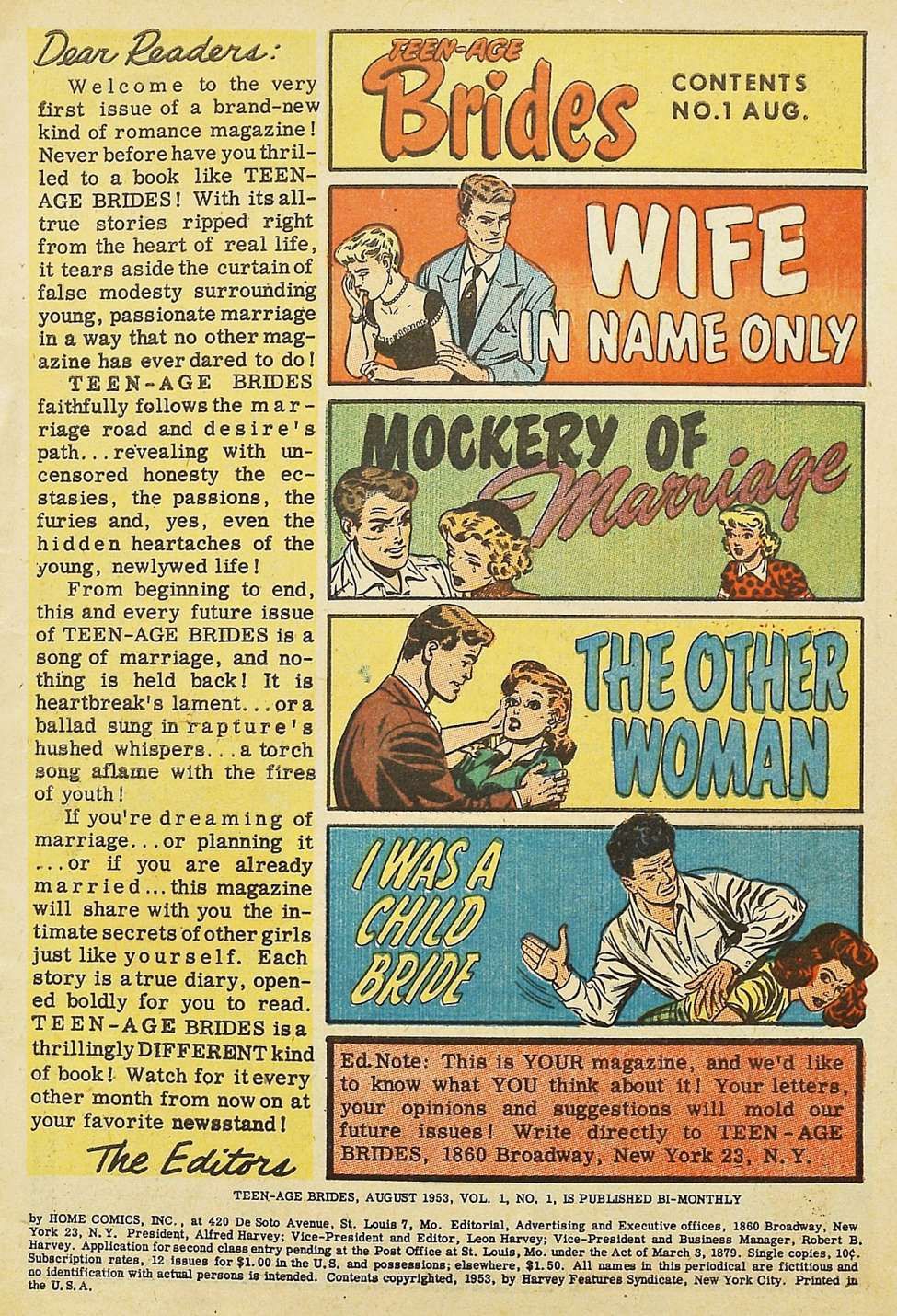

It should be of little surprise, then, Teen-Age Brides was another comic magazine of the era. It, like the St. Johns titles, was heavy on romance in ways that would be surprising even to contemporary readers, teen or adult. Launched by Harvey Comics in August 1953, the magazine spanned seven issues over a single year.

The magazine’s first issue included comics titled “Wife in Name Only,” I Was a Child Bride,” and “The Other Woman.”

Again: this magazine, for teenagers, was focused entirely on marriage, with a pro-marriage agenda. But it wasn’t chaste. Peep the letter to readers in the first issue:

Can we take a moment with the image for “I Was a Child Bride,” paired with the editor’s promise to highlight the ecstasies and uncensored honesty of married romantic life? It’s wild to think a magazine like this flew in 1953, as it wouldn’t last a minute today. Full issues of Teen-Age Brides are available online to read, too.

The 1950s era of teen romance comics was but the start, ushering in even more steamy teen love stories in comic form in the 1960s. Get a glimpse of titles like Teen Romances from IW Publishing, Teen-Age Confidential Confessions from Charlton, and Teen-Age Love, another Charlton joint.

Today’s teen media has little to nothing on this era of comic magazines. But one thing that’s clear is how focused these titles were on a singular demographic that comprised the era of teenagers: cishet white middle class teens and, even more specifically, teen girls. An interesting thing to consider, too, given how comics themselves have been traditionally marketed and how, rather than calling these titles comics, they were instead packaged as magazines…despite being comics.

Want more? I recommend diving into Francis Booth’s Girls In Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Women’s Novel. This work of nonfiction was greatly helpful for exploring this topic, but it’s much more expansive in its view of (white) teenage-hood in the era of the teenager, with plenty more fascinating comic and magazine anecdotes.