10 Things You Should Know about the Crusader Bible

Imagine a book that tells the stories of the Old Testament in pictures and ends up being one of the most important sources in understanding how people spoke and wrote centuries ago.

Imagine a book that is commissioned by a Christian saint who participated in two Crusades and ends up as the prized possession of the enemy he fought to defeat.

Imagine a book that set out to tell the stories of the ancient civilizations of the Bible and instead tells a detailed story of its own contemporary society.

There is such a book. It is commonly known as the Crusader Bible.

Here are ten things you should know about the Crusader Bible.

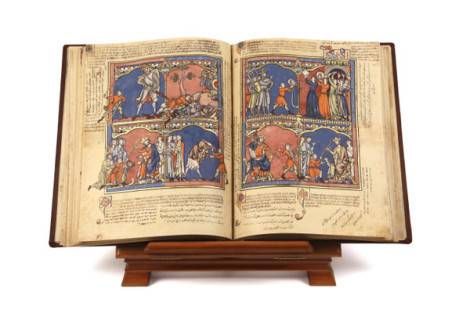

1) The Crusader Bible was created sometime between 1240 and 1250 as a picture book. A total of 46 double-pages have survived to our time containing several hundred illustrated episodes from the Old Testament, from Genesis to King David.

2) The Crusader Bible gets its name from Louis IX, who is believed to have commissioned the work. Louis IX was king of France between 1226 and 1270 and participated in the Seventh and the Eighth Crusades to the Holy Land. In 1297, Louis IX was canonized as a saint and is since then also known as St. Louis. The city of St. Louis, MO, is named after him.

3) The images of the Crusader Bible are considered to be the finest example of French Gothic art. They tell the stories of the Old Testament but the setting is thirteenth-century France, which makes the Crusader Bible not only a beautiful work of art but also an important visual source to the history and culture of medieval Europe.

the pin

Scene of warfare from the Crusader Bible.

4) The Crusader Bible contains images of medieval warfare so detailed and colorful that the battle scenes could potentially be staged as medieval reenactments. The images also contain scenes of other violent acts, as well as love and envy.

5) Originally, the Crusader Bible contained no writings. However, the book is believed to have been brought to the court of the kingdom of Naples by Louis IX’s younger brother, Charles I of Naples, where explanations were added to the images in Latin.

6) After its move from France to Italy, the Crusader Bible disappeared from the historical sources. It didn’t resurface until the seventeenth century when it came into the possession of Polish cardinal Bernard Maciejowski in Kraków, Poland. Because of Cardinal Maciejowski, the Crusader Bible is also known as the Maciejowski Bible.

7) The Crusader Bible didn’t stay in Cardinal Maciejowski’s possession for long. In 1608, it was given to Shah Abbas I of Persia (r. 1588–1629) as part of a diplomatic mission on behalf of Pope Clement VIII. Abbas I ordered that another set of explanations should be added to the images, this time in Persian. Because of Abbas I, the Crusader Bible is also known as the Shah Abbas Bible.

the pin

David and Goliath as depicted in the Crusader Bible.

8) In 1722, the Persian capital of Isfahan fell to invading Afghan forces and the royal library was scattered. The Crusader Bible is believed to have been sold to a Jewish buyer, whose identity is unknown. Following this sale, a third set of explanations were added to the images, this time in Judeo-Persian, which is the language spoken by Jews living in Persia.

9) Once again, the Crusader Bible disappeared from the historical sources. It resurfaced in the nineteenth century as an item on the Western art market.

10) In 1916, 43 of the surviving pages were bought by the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City. An additional two pages are kept at the Bibliothéque Nationale in Paris and one additional page is kept at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

The Morgan Library and Museum’s pages of the Crusader Bible are currently on loan to the Blanton Museum of Art at The University of Texas at Austin. The pages will be exhibited there until April 3, 2016.

If you live in Los Angeles, the J. Paul Getty Museum is hosting a lecture on the Crusader Bible with scholar and expert Sussan Babaie on April 19, 2016.

The Crusader Bible can also be viewed online through the Morgan Library and Museum’s online exhibition.