14 Books in Translation from Western Africa

I’ll scream it to my final day: we need to translate more fiction from around the world into English, particularly fiction from authors of color, queer authors, and otherwise marginalized authors. Every time I make one of these lists I’m stunned and annoyed by the number of “classics” that were never translated or are out of print.

For this list, I used the definition of Western Africa that includes: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Côte D’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo. I tried to include at least one book from every country, where I could.

Keep in mind that I have only included translated works in my consideration, so books that were originally written in English wouldn’t be eligible — this took away from my inclusion of many Ghanian books such as Changes: A Love Story by Ama Ata Aidoo or The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born by Ayi Kwei Armah; as well as many Nigerian books, including the classic Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, or Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth by Wole Soyinka.

Many if not all of these novels engage the history of imperialism in this region in some way, writing of subverting the hierarchy between colonialist and colonized, drawing on oral tradition, and digging into the social, economic, and class changes forged by the impact of colonialism. As a result of that imperialism, many of these books were originally written in French or Portuguese. Language itself is an integral part of many of them — who can write and who can not, who can tell the stories, the power of language, and the ability to write letters across distances.

Many of these books focus on the dependence of women on men within patriarchal systems of marriage, capitalism, and reproduction — on the impact on wives, mothers, and daughters, and on how those women attempt to reclaim power for themselves.

Enjoy these 14 books from Mauritania, Togo, Mali, and more. Put them on hold at your local library and buy them at your independent bookstore. Make it clear that we want to read books in translation — and that publishers can, and should, invest in new translations of books from this region.

Please note that while I took great care to list content warnings where I could, things can fall through the cracks. Please do additional research on the recommended titles if needed.

The Desert and the Drum by Mbarek Ould Beyrouk, translated from French by Rachael McGill (Mauritania)

Young Rayhana is fleeing her Bedouin tribe in an act of rebellious rage, carrying their sacred drum on her back as she escapes toward the city. Scarred by the patriarchal system’s treatment, Rayhana is determined to leave a mark on the tribe that caused her so much emotional trauma. But now she must enter the metropolis and find a needle in a haystack, and as she searches for a person who once treated her kindly, she finds the modern world tangling and pushing against the Bedouin world she grew up in. And since she stole the drum, her tribe is pursuing her, determined to get it back. The book is the first from Mauritania to be translated into English.

Content warnings for rape/sexual assault and sexual coercion, suicidal ideation, depression, sex shaming, homophobia.

Sin is a Puppy that Follows You Home by Balaraba Ramat Yakubu, translated from Hausa by Aliyu Kamal (Nigeria)

The short version of this book’s summary is “men ain’t sh*t.” Alhaji Abdu neglects his wife and children, spending all of his money on himself and forcing his wife to earn her own money to feed their kids. When he decides to take a second wife, he kicks them out, expecting that his success will continue to be guaranteed.

This book highlights the forced dependence of women on men within the patriarchy and how it can become a corrupting force, because women’s power can only be exerted through their manipulation of their man and the pushing down of co-wives. In this book of irony, black magic, and jealousy, men are constantly losing their senses while women remain in strong, determined control through the worst of it. It is infuriating, and impossible to put down.

Yakuku’s book is the first published English translation of a complete novel written in Hausa. The author is a pioneer of soyayya, or “love literature,” as well as a screenwriter, director, and producer.

Content warnings for neglect, domestic abuse, violence, misogyny.

The Ultimate Tragedy by Abdulai Silá, translated from Portuguese by Jethro Soutar (Guinea-Bissau)

Ndani sets out from her village determined to find a better life, condemned for being too unlucky. She finds a life as a maid but is foiled by the machinations of Portuguese colonialism and the cruelties of the mistress and master of the house. The book is full of unjust twists and turns, as Abdulai tries to find a place for herself in a racist and painful world but slowly loses hope that her life will be anything but an unending tragedy.

The book is the first novel to be translated into English from Guinea Bissau.

Content warnings for racism, sex shaming, sexual coercion/harassment.

Doomi Golo: The Hidden Notebooks by Boubacar Boris Diop, translated from French by Vera Wülfing-Leckie and El Hadji Moustapha Diop (Senegal)

In this epistolary novel, an old man named Nguirane Faye writes journals addressed to his absent grandson, Badou, who has migrated somewhere unknown. In a district of Dakar in Senegal, he writes his story, as well as the story of his neighborhood, his country, and its hidden secrets, horrors, and joys. He sits under a mango tree and writes about the loss of his son, Assane Tall, Badou’s father. In the absence of Badou, unable to share the stories with him orally, he does his best to capture them in writing, having faith that after his death, he’ll be able to somehow talk to his missing grandson.

Doomi Golo was the first full-length novel written in Wolof to be translated to English — but with a go-between. Diop actually rewrote the book in French, providing a translation of sorts, that was then translated into English.

Content warnings for ableism, rape, sexual harassment, body horror, reference to genocide.

In the Company of Men by Véronique Tadjo, translated from French by Tadjo with John Cullen (Cote D’Ivoire)

In this book, Tadjo captures the Ebola virus and its devastating impact and spread in snapshots based on real accounts. An ancient baobab tree, a doctor, a volunteer at the hospital, a young survivor of the disease, the bats: all get to be narrators, speaking in their own voices from their own unique perspectives of the devastating event. They all paint a picture of the painful reality of a pandemic, of chlorine spray and prayer, of the people who put their lives on the line and the prejudice and misinformation that spread throughout the cities, of the environmental connection between our natural world and social and health issues.

Content warnings for pandemic, death, gore, neglect.

The Parachute Drop by Norbert Zongo, translated from French by Christopher Wise (Burkina Faso)

Norbert Zongo was a journalist and editor who exposed corruption in the government and was assassinated after L’Indépendant started investigating a murder connected to the regime. This novel was incredibly subversive. In it, Zongo writes of the corrupt President Gouama in fictional Watinbow, who tries to sabotage two senior officers who are planning to overthrow him.

The book is a clear look at the devastating impact of despots and their corrupt nature and violent reigns — and a thinly disguised critique of Togo’s President Gnassingbé Eyadema, serving as a foil for Burkina Faso’s own government of the time as well. In the preface in 1988, he says he was beaten up for writing the book. The case of Zongo’s murder was closed in 2006 to outrage, and in 2014, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights ordered Burkina Faso’s authorities to investigate the case properly and compensate Zongo’s family.

An African in Greenland by Tété-Michel Kpomassie, translated from French by James Kirkup (Togo)

Kpomassie discovered a book about Greenland when he was still a teen in a small village in Togo. From that moment, he was determined to make it there, and while it took a decade of traveling from country to country, picking up jobs to complete each leg of his journey, he was finally able to reach Greenland — and he loved it. This memoir is a travel story, an adventure story, and a book about discovery and leaning on the people you stumble on along your way. He travels to the farthest north of Greenland to meet Inuit people, and discovers a lot about their lives and culture. It’s a fascinating book, well worth the read.

Content warnings for xenophobia, racism, alcoholism, substance abuse, domestic violence, animal death.

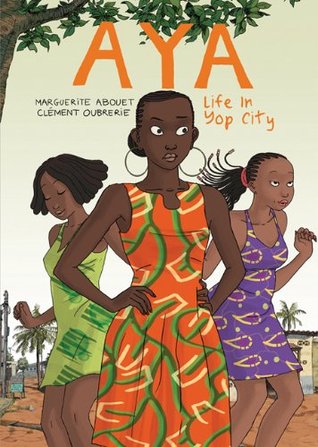

Aya: Life in Yop City by Marguerite Abouet, translated from French by Helge Dascher, illustrated by Clément Oubrerie (Côte d’Ivoire)

In this first half of a vivid, award-winning series by Abouet, we follow three young women — the hard-working, practical Aya, and her pleasure-seeking, easygoing friends Adjoua and Bintou — through their lives in their busy, gossip-filled neighborhood in 1978 Côte d’Ivoire. We get to see the twists and turns of relationship drama, secrets revealed, unexpected pregnancy, betrayal, hearts broken, and more, all in the vivid colors and expressive artwork of Oubrerie. Behind the fun and chaotic drama of the neighborhood lie young people dealing with issues of structural patriarchy, parental and cultural expectations, and misogyny. I can’t wait to read volume two!

Content warnings for domestic violence, sex shaming, misogyny, sexual harassment, homophobia.

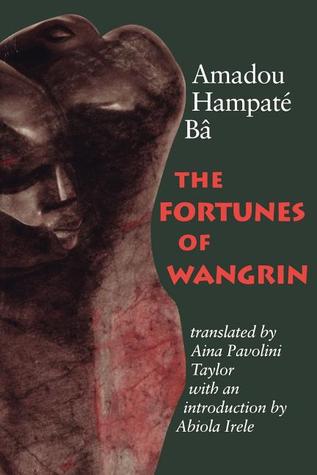

The Fortunes of Wangrin by Amadou Hampâté Bâ, translated from French by Aina Pavolini Taylor (Mali)

Wangrin is an interpreter serving the French colonial administration as it establishes itself in West Africa. Smart, cunning, and dangerous, he is hungry for wealth and power, and determined to get it. If Wangrin’s antics and intricate political plots were all that were in this book, it would be enjoyable enough, but the fact is that Wangrin is also generous — he is proud to say he only cheats the rich and powerful — making this a great book about a compelling anti-hero.

Bâ has emphasized that this book is about a real person who shared his stories with the writer when he was a young child. Fortunes draws on oral tradition, folklore, and the impacts of colonialism.

Content warnings for fatphobia, lynching threat, racism, the n-word, violence, sexual coercion, drugging, addiction, alcoholism, suicide.

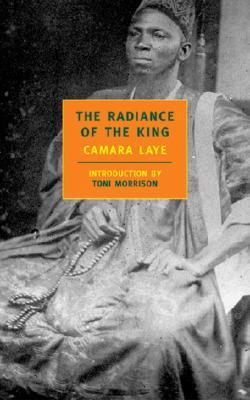

The Radiance of the King by Camara Laye, translated from French by James Kirkup (Guinea)

Toni Morrison writes a superb introduction to this modern classic, a story about a Western white man named Clarence who is stuck in a tough spot on the African coast. He owes money from gambling debts. His plan? Demand to see the king, and offer him Clarence’s services. What those services are, he doesn’t know, but surely the king will want to see him, a white man, and get his advice. A beggar and two chaotic boys “adopt” Clarence and promise they’ll find a way to get him to the king. But can he trust them?

Clarence expects to be able to access and comprehend Africa better than the people around him, but quickly finds that he is the one who is completely lost in the machinations of what’s happening around him. It plays with his gaze, of what he sees and what he chooses to hear, as he is pulled around and manipulated.

Content warnings for sexual assault, drugging, racism.

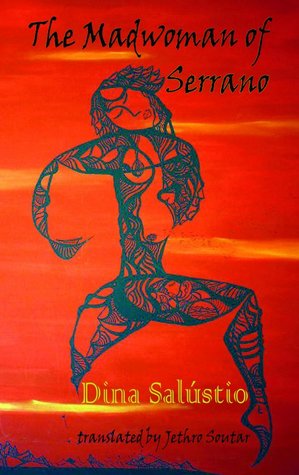

The Madwoman of Serrano by Dina Salústico, translated from Portuguese by Jethro Soutar (Cape Verde)

In the rural village of Serrano, patriarchal power and suspicion rule, and a madwoman roams, babbling, around town. But is is nonsense, really? Or is she just a woman whose words no one wants to hear? She befriends Filipa, the daughter of villager Jerónimo and a mysterious stranger who once fell from the sky and later disappeared. It’s a strange and wondrous story that digs into all the BS of toxic masculinity, all the damage it does to people of all genders. As a now-grown, successful Filipa looks back on her childhood from the shelter of the city, the novel digs deep into the insularity and secretive community of this small town. This was the first novel by a female author to be published in Cape Verde.

Content warnings for sexual coercion and assault, misogyny, domestic violence.

The Belly of the Atlantic by Fatou Diome, translated from French by Lulu Norman and Ros Schwartz (Senegal)

A young boy named Madické is determined to succeed as a soccer star, just like his Italian idol Maldini. His sister, Salie, an expat in Paris, answers his calls but continues to insist that he should stay home, unable to explain to him the pain of trying to make it as an immigrant in France. As they bicker, Diome unfurls a larger narrative, revealing a web of stories caught in the community of the Senegalese island of Niodior — from a former soccer star to an exiled schoolteacher. The book is at turns funny and charming, and desperate and sad. It’s vividly written throughout, capturing the insidious dynamics of power, colonialism, and race, and the stubborn striving of young people determined that football can be their way out.

Content warnings for sexism, transphobic language, the n-word, racial slurs, misogyny, deportation, sexual assault, racism, xenophobia, domestic abuse.

The Epic of Askia Mohammed recounted by Nouhou Malio, translated from Songhay by Thomas A. Hale (Niger)

This is a transcription, word-for-word, of an orally shared epic, performed by griot Nouhou Malio over the course of two nights in a small town in Niger. This epic poem shares the life of Askia Mohammed, the ruler of the Songhay empire who came to power in 1493, and the story of some of his descendants. Among other things, Mohammed is remembered for spreading Islam in West Africa. The epic includes stories of war, love, assassination, and magic (from hovering cities to carefully crafted spells). It’s captured very, very loyally to the original oral telling, and that gives it a special magic.

Content warnings for violence, war, animal death.

So Long a Letter by Mariama Bâ, translated from French by Modupé Bodé-Thomas (Mali)

Recently widowed woman Ramatoulaye Fall writes letters to her lifelong friend Aissatou, who now lives independently in the U.S. Ramatoulaye is smarting from the devastation of her husband’s actions — before his death, he took a second wife and essentially abandoned his first family. In this short novel, just 95 pages, Bâ breaks apart the “new Africa” and how it has failed to carry women along with its wave of modernity. An educated schoolteacher, Ramatoulaye is still caught in an impossible web of polygyny, societal dependence, and patriarchal exploitation of women. Not only does Ramatoulaye herself feel real, but her letters are a beautiful expression of female friendship and a call for independence and bold choices.

Content warnings for misogyny, adult/minor relationship, forced marriage.

For recommendations for Nigerian literature written in English, check out this list of fantastic Nigerian books.

Want more books in translation content? I have lists for you of books in translation from Catalonia, Argentina, France, Mexico, Central Africa, Japan, Southeastern Europe, Brazil, Ukraine, Sweden, and China. If you have recommendations or requests for future lists of books in translation, or if you want me to know about a book I missed, please let me know on Twitter!