Kelly Sue DeConnick: Smashing the Patriarchy and Reaching New Audiences

Kelly Sue DeConnick is a force in comics. In her work, she tackles tough issues surrounding love and loss, life and death, sexism and racism—and she’s also really fun to follow on Twitter.

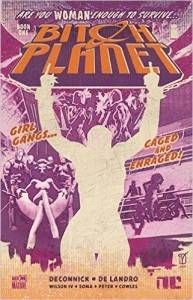

She is the writer behind Pretty Deadly, with art by Emma Rios, colors by Jordie Bellaire, edits by Sigrid Ellis, and letters by Clayton Cowles. And she writes Bitch Planet with artist Valentine De Landro, colorist Kelly Fitzpatrick, letterer Clayton Cowles, designers Rian Hughes and Lauren McCubbin, and editor Lauren Sankovitch.

I spoke with Kelly Sue recently about new ways to read her work, how the messages of her books compare to recent events, and how creative teams work together to produce diverse books. Our conversation below has been edited for clarity and length.

Melody Schreiber: Comixology is adding several new Image titles to its reading service, Comixology Unlimited—including Bitch Planet. Will this open up your work for new audiences and provide new avenues for your work to be read?

Kelly Sue DeConnick: I don’t really know! I guess we’ll see. I have a concern, always, about fidelity to our brick-and-mortar retail partners, and getting people into comic book stores. But I am assured that it’s for the most part bringing new readers in who may then make the transition to brick-and-mortar stores, rather than taking people out of brick-and-mortar stores. For new readers, this is a way to get them over the hump. It’s a little easier than finding a store and trying to navigate comics.

MS: This way, people can read a book and feel like they know something about comics before they even set foot in a store, which can be an intimidating experience.

KSD: Yes. Communities are really appealing, and it’s a really fun way to enjoy a hobby—to take it to the level of something social, to get involved in events at your local store or discussion groups. That’s a really fun level-up. But it is a level-up for most people who are coming in brand-new, and sometimes it is a little intimidating. Being able to start with Comixology Unlimited, where you’re like ‘I’m going to try a whole bunch of different titles and see which ones stick for me, which ones I like.’ Hopefully that becomes [laughs] the gateway drug.

MS: Are you looking to reach certain audiences—for instance, would you like to make women feel more at home in comics communities?

KSD: Sure? Absolutely, but I think women are as many and varied as our numbers. My book isn’t going to be for all women, any more than any book is.

Women are coming back to comics in large numbers without my help. And it’s also important to me that we be very clear that this is women returning to comics. Women have always read comics. Really, let’s be honest, what we’re talking about is shared-universe comics when we say that comics haven’t been for women. Our memory is very short when we have that conversation.

We’re really looking at the ‘80s and ‘90s, that pushed a lot of women out. And it was an active choice. Comics were being used to sell toys, and they were being aimed particularly at little boys or young men—in ways that were actively insulting to women. So women left, because that’s what you do when people actively insult you.

The young women coming to comics now may have never read comics before. But in the ‘40s and ‘50s, there were comics geared for women, young women, that had circulations of half a million copies a month. So, this isn’t a new idea that women should read comics.

KSD: It’s a satire, and satire has to be grounded in truth. If you’re satirizing something that doesn’t exist, it’s really not funny. What’s been happening lately in the real world with the more pointed and virulently misogynistic rhetoric—in many ways, the New Protectorate is much milder than that.

We’re satirizing the condescending “good-father” patriarchy. Ideas like, ‘We know what’s best for you. Do as you’re told and you’ll be happier. We’re infantilizing you because we love you.’ The person we’re aiming at, the one we’re trying to make uncomfortable, is the guy who thinks ‘I love women! I’m not part of the problem!’ And women can participate in that as well. The guy who’s sending me rape threats on Twitter or whatever – that dude is not my headache. I don’t care. It’s the guy who thinks he’s a good guy, that I’m aiming to make uncomfortable.

And I want to be clear, too, that this works with race as well. I am a white woman. Until I accept and understand my role in a racist culture and how I have contributed—even when I thought, ‘I love black people! I’m not part of the problem! I’m not a racist!’ No, you are a racist, you are white and you are part of a racist culture. Sorry!

The only thing you can do is become aware of it. Try to find your biases, examine them, see how you can change your behavior, and police your own culture. You don’t get to be passively resistant. That’s a myth.

MS: Going back to recent events, they seem like a wake-up call for some people—that you do need to be actively resistant, that injustice is alive and well and you have a responsibility to act when you see it.

KSD: The idea that racial issues in our society are something that we need to let black people handle. No! We must engage, as white people. We have to examine our own behavior. We need to understand. They understand! They’re not the ones who need to change. It’s the same where gender is concerned. Men need to engage in the study of sexism and the fight against sexism in our culture because they are the ones whose behavior needs to change.

That said, nothing in our book aims to put answers out there. If I thought I could fix these things, I wouldn’t be writing books—I’d be running for office. Making art is about putting questions out into the world, and not answers. I think our book becomes preachy and dull when it starts to veer toward thinking we know what the answers are. We have treaded into those waters a couple of times, and we have to gently course-correct.

MS: This speaks to what you said earlier—that we’re not talking about a monolith here. The experiences of women and people of color are all different, so there will be many answers to many different questions. To try to have one book answering all of them would be a fool’s errand anyway.

KSD: Indeed. I ain’t that good.

MS: I know it’s really important for you to view these titles as the work of a creative team—not just you working with underlings.

KSD: Absolutely!

MS: Why is that so important?

KSD: Because it’s true. We are in an age right now where writers are getting more credit for our books than is appropriate. Because of the way corporate comics are structured and how quickly we have to put comics out—a writer can, theoretically, write a comic much faster than an artist can draw one. So, in corporate comics for instance, we’ll keep one writer on a book and identify that writer with the book, but then we’ll change out the artists. We start to see the consistent voice as the writer’s voice. It’s not a mean-spirited ‘artists don’t do creative work’—it comes from this practice we have that’s started to affect the way we think.

But in truth—and this is true with me even more than with most writers, because I don’t have a particularly visual imagination—all of my books are co-created. Bitch Planet wouldn’t be Bitch Planet without Val. Even when we have another artist—like on the biography issues we’ve had with Robert Wilson IV and Taki Soma, where we focused on the backstories with Penny Rolle and Meiko—Valentine was still involved with that production process. He has created the visuals of this world. It is as much his vision as it is mine.

Also, Val and I make good partners on this book because we both have areas where we have privilege and areas where we have bias. I am a white woman, and he is a black man. It’s a very good match for this particular book, to explore those questions of bias and privilege. We’re able to bring our own fury and our own honesty to those issues. And he’s incredibly talented, and I love him dearly.

This is equally true of Pretty Deadly. Everyone is contributing their artistic skill set to the production of this book. The book would be changed by switching out any of those people. The artist and writer are the two who tend to spend the most time deep in that story, they pay the highest price for the creation of that story, and I think that’s why they get most of the credit and generally share ownership. But everyone else has a very significant contribution that I don’t think we always recognize.

Pretty Deadly without Jordie would not be Pretty Deadly. Pretty Deadly without Emma would be garbage.

MS: It seems like a good way for artists to break into the industry and get recognition.

KSD: Everyone does work for hire. It’s an important tool to have in the toolbox. I wouldn’t trade my time on Captain Marvel or Avengers Assemble for anything in the world. I learned a ton; I absolutely loved it.

The way those businesses are structured—those books come out regularly. I cannot say that of Pretty Deadly or Bitch Planet—although we are, I swear to God, working on it. But we have lives and things happen. With a corporate comic, when something happens and somebody can’t work for one reason or another, they’re replaced. We don’t do that. If something happens and a member of our team has to deal with a family emergency, the book stops. That is a choice we have made. It hurts our bottom line, but it is more important to us, for what we value about the product.

Someone is going to read this, and interpret it as me being nasty about comics that aren’t structured that way, and that is not the case. There are wonderful, amazing comics that come out in shared universes where the artists and writers are regularly switched out.

This is just what works for us and what is important for us. Absolutely it hurts us on the financial end. But it’s the decision we’ve made, and we stand by it. We’re hoping, someday, to have our cake and eat it too.

MS: Barring future emergencies, have you gotten some of the timing issues ironed out, or is it still a work in progress?

KSD: Pretty Deadly is moving much faster. We have focused on taking time off between arcs, to make more time for other projects. But we’re back. The third arc is in production right now, pages are coming in—they’re stunning.

With each of these books, we were creating an entirely new world, and an entirely new visual language for us. There’s a lot of stuff that you have to figure out at the beginning that’s very time-consuming. But we’ve figured out a lot. Pretty Deadly moves much faster now. Five issues, monthly, and then there’ll be a break, and then the fourth arc. We don’t know how long that break will be, but we don’t want the break between two and three to be as long as the break was between one and two.

Bitch Planet, we’re taking time off to get ahead again. We had a couple of really hard blows that knocked us way back. But in the time we’re taking off to get ahead, we have put into production the Bitch Planet anthology. We will have something on the stands so people will still get the fix, but we won’t be returning to the main narrative until the third arc.

Thank you to Kelly Sue DeConnick for taking the time to speak with us!