I Still Got My Eyes on the Prize

I have a vivid memory of the day we were taught about slavery in elementary school. It’s not a good memory, not a happy memory. Slavery is a confusing lesson for kids (hell, it continues to confuse me) creating an “us versus them,” black vs white lesson that comes out of nowhere to disrupt the innocent friendships and bonds we’d created between ourselves.

What I recall from the lesson that day was just division and chaos: We owned you. They owned us.

The shame, the fear, the confusion, just the absolute confusion. Going home to my parents, crying, asking if it was true. Did my white friends own us?

The world fractured on that day, and I’m still trying to put the pieces back together.

***

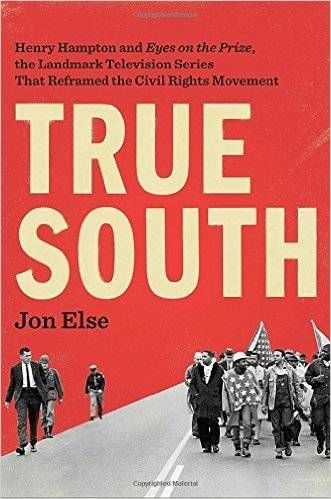

Eyes on the Prize is PBS’s documentary series about the behind the scenes stories of the Civil Rights Movement. I was introduced to it as a rainy day just-keep-busy history lesson from my favorite teacher, still hippy after all these years. It quickly became so much more.

From the titular theme song, a converted negro spiritual adopted over the ages to suit needs from chain gangs to cotton fields to TV shows; to the images –barking dogs baring their teeth, fire hoses turned on full blast, the lifetime of short steps to a school house door, peaceful marches, and anger, so much anger — and the words, most of which continued to reverberate in my heart long after the VCR stopped and the lights came back up in the classroom.

“I know the one thing we did right / was when we began to fight.” I still get chills.

Eyes on the Prize premiered in 1987, but to a young black girl in Southern California growing up in a rainbow bubble carefully crafted by my hardworking parents — my mom the daughter of a domestic, my dad the son of a garbage man, both educators and both hell bent on making sure their children’s lives were nothing like their own — the stories depicted in the series might as well have been from the previous century, another world.

Rosa Parks and Emmett Till.

Lunch counter sit-ins and Freedom Rides.

Segregated schools, segregated bathrooms, segregated water fountains, segregated restaurants, segregated housing.

Detroit. Mississippi. Selma. Watts. Montgomery. D.C. Chicago. Attica.

Black Power.

It’s an entire movement broken into digestible hours. A lesson in perseverance. The birth parent of Black Lives Matter.

Eyes on the Prize brought to life the young adult books that I was reading at that time, books like Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry; the history books I was using in school books that taught me as much as they scarred, and scared me. It brought to life an entire movement that I’d only read about in books, or heard stories about from family:

Black kids like my father could only swim in the local pool right before it was cleaned for the white kids.

Black kids like my mom learned early on why their adults stayed armed at home.

Eyes on the Prize gets a pass as maybe the one time I’ll recommend TV over the books.

It couldn’t have come at a more important time.

Eyes on the Prize and all of its stories are my reminder, in 2017, of the continuing importance of Black History Month. Of why we fought and marched and protested, and continue to. What was won, and what is still to come.

This phrase is oddly commonplace now. We laugh about it, hashtag it, use it as the butt of jokes about bad hair days. Please remember that it has deep meaning, that people died and continue to die for it. The dream is not a reality yet.

The struggle continues.