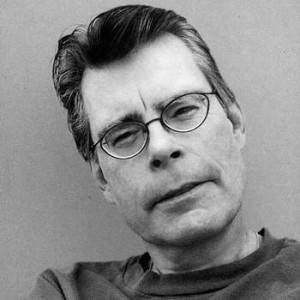

Breaking Up With Stephen King Is Hard To Do

I’ve been trying for awhile now to break up with Stephen King. It’s not him, it’s me–well, maybe also, it’s a little him. I know that Mr. King can be a damned good storyteller; I still love Carrie, Pet Sematary, The Shining, the Dark Tower series. His character work surpasses just about any author, non-literary or otherwise.

So, when I critique Stephen King, it’s from the place of a person who was a fan and who can still appreciate his work, not from the place of a person who looks down her nose at the Big Mac of literature.

Even after I moved on to literary fiction in high school, I would regularly revisit King’s work. Over time, I was less able to overlook flaws in his books, like his notoriously bad endings and his heavy-handed themes. That part was all me: I had grown out of our relationship and it’s not fair to expect from Stephen King what I had started getting from writers like Salinger, Hurston, and Kerouac. I stopped buying his newest works on release day, though I often got around to them eventually.

I noticed that King’s books were getting longer, and longer, and longer. It seemed his editors were on permanent vacation, leaving his stories bloated and meandering. Gone were tight, intense thrillers like Carrie; instead, we got Under the Dome, which led you down a 1074-page path to one of the worst endings that King has ever written. 11/22/63 suffered a similar fate: excellent concept, not-amazing execution with pacing problems, excessive foreshadowing, excessive use of repetition and heavy-handed themes, and a general lack of organization and payoff.

His strengths are present in both books: nobody can burrow into the mind of a psychopath like Stephen King. Few authors can take a cast of characters, throw them into some seriously fucked-up circumstances, and work the magic that Stephen King can with them. It’s just getting harder and harder for me to look past the lack of editing, and the sense of arrogance that I get from King about his work.

Yep, arrogance. I first noticed it when he re-made The Shining into a miniseries. The series was supposed to “fix” Kubrick’s vision of the novel, hewing more closely to the original story; King has frequently been vocal about his disappointment in Kubrick’s adaptation. I had a few issues with the adaptation myself, so I gave the miniseries a shot; I was shocked to see that King had made some significant story revisions himself, right off the bat: Jack was now in AA and Wendy was threatening to leave him within the first fifteen minutes or so of the series.

Um.

Neither of those things did happen in The Shining, nor would they have happened. The script may have been closer to the original plot, but he fundamentally changed his own characters and called it “truer.” With this in mind, when he started talking about rewriting the Dark Tower books, I felt fear. If, after twenty years, he thought that Jack Torrance would have gone to AA, what would he do to Roland and company?

I felt that King was trying to cover up his writing past, but for me, that’s where his best work lies–and maybe he’s uncomfortable with the person that he was when he wrote a lot of those novels. Maybe he’s uncomfortable with Jack Torrance because it hits a little too close to home. But I’ve been a reader of his for a long time; he can’t rewrite history and expect me to forget- that insults my intelligence. Eurasia hasn’t always been at war with Oceania.

Still, I find it hard to break up with Stephen King. I read his work for so long that his voice is threaded into my psyche; his words visit me often, like an old friend–or, perhaps more appropriately, a ghost. A new book comes out and I think, “Well, maybe this one will be different.” I’m still waiting for the magic to come back.