The Tale of The Dueling Neurosurgeons Will Teach You Gross Things

Did you know your brains are the consistency of ripe avocado? That they can be spooned up like tapioca? That throughout history the greatest advancements in neuroscience have been made through war, disaster, and quasi legal experiments on people with mental illness? Oh, and we all know the story of Phineaus Gage whose skull I have seen, because they have it at Harvard, where my husband teaches biology in the summer: there’s a hole in that donut.

Gage is the guy who survived a 3-foot long railway pike through his head like something out of Stephen King, and also like something out of Stephen King, the accident changed his personality. He used to be affable and focused. Afterwards, he was angry. Prone to outbursts. From this scientists learned localization. Also, from probing at the brain with a spatula, as they did in 19th-century France. I am so freaking glad I don’t live in 19th-century France. I shiver to wonder what we’re doing now in the name of science that will seem barbaric in a hundred years.

Scientists learned there were areas associated with language, others with emotion, and memory. There was fierce infighting as the brain was slowly mapped. Keane tells these tales with relish. He rightfully belongs on anyone’s list of Best Science Writers. Like another of my favorites, Mary Roach, he’s funny, he’s not squeamish, he explains complexity carefully. But I had trouble with Andreas Vesalius, the 16th century “neurosurgeon” (the word didn’t exist; he was basically a barber, and a sicko) for whom “dissection was as much a tactile as a visual pleasure.” Gross.

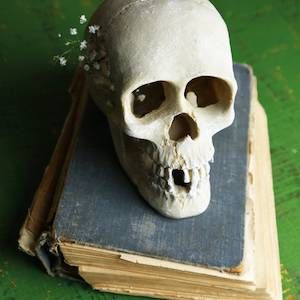

However, Vesalius’ enthusiastic human dissections form the basis of “one of the most beautiful scientific books ever published,” On The Fabric Of The Human Body, the first set of realistic drawings of the human form, inside and out. The Italian Renaissance artist Titian did the backgrounds. So cadavers frolic on Italian hillsides, and, in one of the most famous drawings, a standing skeleton considers a skull “Poor Yorick”-style on an gorgeous marble table like something out of Architectural Digest.

____________________

Expand your literary horizons with New Books!, a weekly newsletter spotlighting 3-5 exciting new releases, hand-picked by our very own Liberty Hardy. Sign up now!