“We’re All Mad Here” – Lessons from Alice

This is a guest post by Jessica Tripler. Jessica is an academic who lives in Maine. She’s enthusiastic about digital reading, both e-book and audio. She can’t resist marriages of convenience, waning trends, or any novel with a philosophical subplot. Since 2008, she has blogged at ReadReactReview whenever life, by which she means Twitter, doesn’t get in the way. Follow her on Twitter @RRRJessica.

_________________________

I came home from elementary school one early spring day to find the front hall jammed with moving boxes. Within hours, I was in a new house in a new town, trying to figure out what the heck happened. Sent outside to play, I was standing under a maple tree watching helicopter seeds spin to the ground when an elderly woman appeared and introduced herself. She was our neighbor, but she became much more than that to me and my newly divorced mom. A month later, on my birthday, she gave me a book.

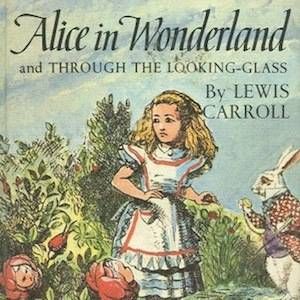

I’d always read a lot, and I liked Nancy Drew, Harriet the Spy, and Sheila the Great. But Alice, I discovered within two pages, was my soul mate. She found herself in a strange world with no idea how she got there or whether she’d get back. She questioned everything, even her own identity: “I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.” My confusion felt passive, even paralytic, but hers came off as intelligent, galvanizing curiosity.

Author Lewis Carroll described Alice as loving, gentle, trusting, and courteous, and I suppose that’s all true, but I read her a little differently. She sees a talking rabbit with a pocket watch and believes her own eyes. She jumps down a rabbit hole so deep she has time for bizarre conversations with herself, plus bonus disappointment with an empty marmalade jar. When she lands, instead of trying to get back up, she sticks to her objective. And she calls it like she sees it. She tells the Mouse he’s easily offended, nearly loses her temper with the Caterpillar, is indignant with the Pigeon, brands the Footman idiotic, and argues with everyone from the Cheshire Cat to Humpty Dumpty. She comes uninvited to the Mad Tea Party, leaves it in disgust, and pronounces it the “stupidest tea-party I ever was at in all my life!” She even silences the Queen with a sharp “Nonsense!” when threatened with decapitation.

But Alice is more than a smart mouth. She’s relentless in trying to make sense of things, even as Wonderland is just as relentless in trying to make nonsense of them. Living in my own topsy-turvy world, the appeal of methodical thinking as a way to bring order to chaos was strong, damn the skeptical adults:

‘Thinking again?’ the Duchess asked, with another dig of her sharp little chin.

‘I’ve a right to think,’ said Alice sharply, for she was beginning to feel a little worried.

‘Just about as much right,’ said the Duchess, ‘as pigs have to fly.’

Alice doesn’t listen to that nonsense. She, I realized with awe, is going to force people to make sense or she’ll make her own sense of them, and it won’t be pretty.

Then, of course, there’s the great finale, which, aside from the fact that Alice is technically sleeping at the time, I’d put up there with The Hunger Games’ Katniss brandishing her handful of nightlock berries. At the Knave’s trial Alice grows larger and larger, all the while questioning those who try to impose their arbitrary rules on her. The image of a seven year old girl looming over a group of powerful but foolish adults was indescribably compelling:

‘Let the jury consider their verdict,’ the King said, for about the twentieth time that day.

‘No, no!’ said the Queen. ‘Sentence first–verdict afterwards.’

‘Stuff and nonsense!’ said Alice loudly. ‘The idea of having the sentence first!’

‘Hold your tongue!’ said the Queen, turning purple.

‘I won’t!’ said Alice.

‘Off with her head!’ the Queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved.

‘Who cares for you?’ said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time .) ‘You’re nothing but a pack of cards!’

I never stopped being interested in the kinds of problems Alice faced in Wonderland: questions about identity, agency, femininity, power, and justice. And I never forgot the importance of open-mindedness, curiosity, and logic in working through them. Alice gave me hope and, eventually, led me to a career in philosophy. I was having a pretty hard time when I met Alice. But thanks to her, at least sometimes, I could believe “that very few things indeed were really impossible.”