How Libraries Respond to Disaster

Late in the night on Monday, a massive storm tore the roof off of the library at the University of Nebraska-Kearney, with pretty dire consequences. “When it opened up, the water just poured into the library from the roof all the way down to the basement level of the library,” the Vice Chancellor for Business and Finance told a local television station. Precise numbers are still unclear, but it’s clear that thousands of books have been either destroyed or damaged by the deluge.

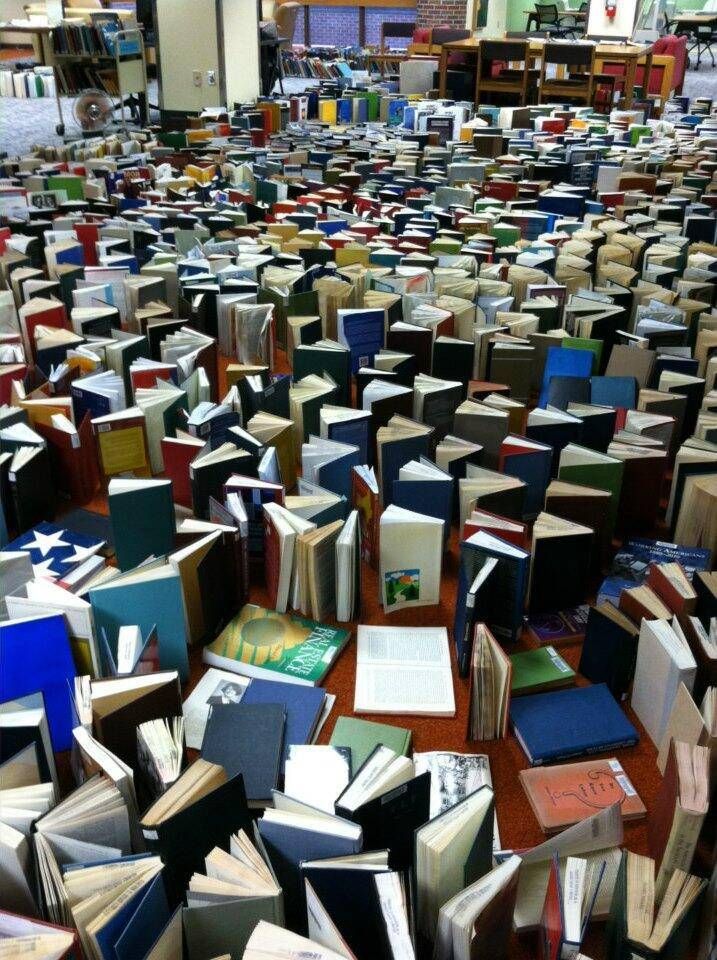

Huge numbers of books have been spread across floor to dry. UNK made a photo of this available, and it’s horrifying (if also oddly beautiful):

As anyone who has had the misfortune of spilling a cup of tea on a book knows, this is disastrous. Warped pages are bad enough, but they’re the least of the problems posed by waterlogged books. More delicate or cheaply-bound books may disintegrate, pages may stick together irreparably, mold may grow and spread. Virtually none of the affected books will ever be the same.

One solution that is sometimes available (unfortunately, it seems, not in UNK’s case) is freeze drying, which initially sounds a bit strange. But it’s true: the process that gives us astronaut ice cream can help preserve waterlogged books. Wet books or papers are conventionally frozen as quickly as possible, and then they spend three to five days in an industrial freeze drier. This very slowly and gently removes moisture, preventing mold growth and allowing pages to be separated more easily. You can see a bookish freeze drier in action at the National Library of New Zealand in this video:

As crucial as these preservation techniques are, the most important—but often most difficult—way that libraries respond to disasters is by maintaining continuity of service. This doesn’t, and often can’t, mean providing service in exactly the same places and in exactly the same ways. (The lack of a roof, for example, tends to prevent business as usual from continuing anytime soon.) But as the Queens Borough Public Library showed in the wake of Hurricane Sandy—by using bookmobiles to bring information and diversion to people in heavily damaged neighborhoods—libraries are far, far more than their buildings. They’re librarians offering help in the midst of trouble. They’re community members gathering to talk and read. They’re stories and information shared by neighbors and friends. They’re resilient and, in the best way, stubborn.

I’m keeping my fingers crossed in hopes that UNK can preserve as many books as possible, but regardless, I know the librarians there will continue to serve their community however they can. Because that’s how libraries respond to disaster.