Culling, Surrendering, and the Old College Try

In the midst of feeling overwhelmed by my own bookshelves, I wanted to take a moment to point you in the direction of a blog post from last April that I just adore: “The Sad, Beautiful Fact That We’re All Going To Miss Almost Everything” by Linda Holmes at NPR’s pop culture and entertainment blog, Monkey See.

The post is, in my reading, about how we as consumers learn to cope with the fact that there are so many things out there that we feel like we should be paying attention to. In the past, there used to be “a limited number of reasonably practical choices presented to you.” When thinking about books specifically, as Jeff pointed out earlier this week, there used to be gatekeepers in place across the publishing landscape to put restraints on the choices we might make. This was useful… but obviously limiting.

Today, however, Holmes notes that “everything gets dropped into our laps,” giving us only two responses to the drive to feel well-read: culling or surrendering. Under her definition, culling is a process of choosing for yourself what is and is not worth your time. It’s a process of making value judgements of one thing over the other in an effort to winnow down the potential options to choose from. Surrender is a different process:

Surrender, on the other hand, is the realization that you do not have time for everything that would be worth the time you invested in it if you had the time, and that this fact doesn’t have to threaten your sense that you are well-read. Surrender is the moment when you say, “I bet every single one of those 1,000 books I’m supposed to read before I die is very, very good, but I cannot read them all, and they will have to go on the list of things I didn’t get to.”

It is the recognition that well-read is not a destination; there is nowhere to get to, and if you assume there is somewhere to get to, you’d have to live a thousand years to even think about getting there, and by the time you got there, there would be a thousand years to catch up on.

Her main argument in the essay was, I think, the idea that our cultural conversation about consumption (of media, defined broadly) is full of people who are more interested in culling than surrendering. By throwing out entire genres, people who cull, in many ways, simplify their choices by arbitrarily eliminating a vast number of the potential choices they might make.

Surrendering is harder. It’s a moment when you have to accept that you can’t read/see/listen to everything, that there are great things that you will inevitably miss. But it’s also the moment, as Holmes points out, that you realize how many great things exist in the world:

Imagine if you’d seen everything good, or if you knew about everything good. Imagine if you really got to all the recordings and books and movies you’re “supposed to see.” Imagine you got through everybody’s list, until everything you hadn’t read didn’t really need reading. That would imply that all the cultural value the world has managed to produce since a glob of primordial ooze first picked up a violin is so tiny and insignificant that a single human being can gobble all of it in one lifetime. That would make us failures, I think.

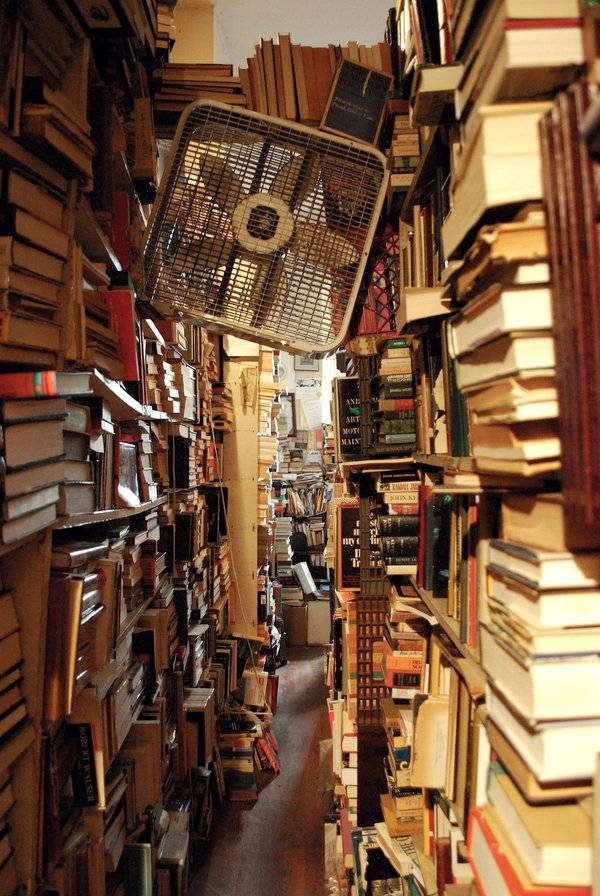

I’ve always found this particular essay comforting, as a reminder that no one gets to read everything. That what I can find time to read and write and talk about is enough. That it’s OK to look at my bookshelves and surrender to the fact that I may never read all of the books, and that my bookshelves themselves are a limiting factor of what I may end up being able to read.

However, I’m still not ready to abandon the idea of culling — within reason, and without judgment of others (which may be the same thing as surrendering). I don’t think there’s anything wrong with admitting that a certain genre or style, in general, doesn’t work for your particular tastes. The problem is when that genre gets dismissed before it’s been given a proper chance. In some cases, a proper chance may just mean one chapter of a book or one episode of a television show, but it’s unfair and lazy to cull an entire section of pop culture without at least giving it the old college try first.

Which finally brings me back around to the point of Jeff’s post — in a new media landscape, it is even easier to find people who can serve as a gatekeeper to a particular genre, suggesting which of the books in that category might be the highest quality and therefore worth trying. If after taking the recommendations of a trusted gatekeeper to heart and trying a few horror novels or biographies or short story collections, you decide those genres don’t push your literary buttons, let it go. Surrender to the fact that there might be quality short stories out there, but that the format doesn’t work for you.

Being well-read isn’t about quantity or even necessarily what you decide to read; it’s about accepting that there are things of quality that you will not be able to consume while still leaving yourself open to pop culture that may be outside of your comfort zone.