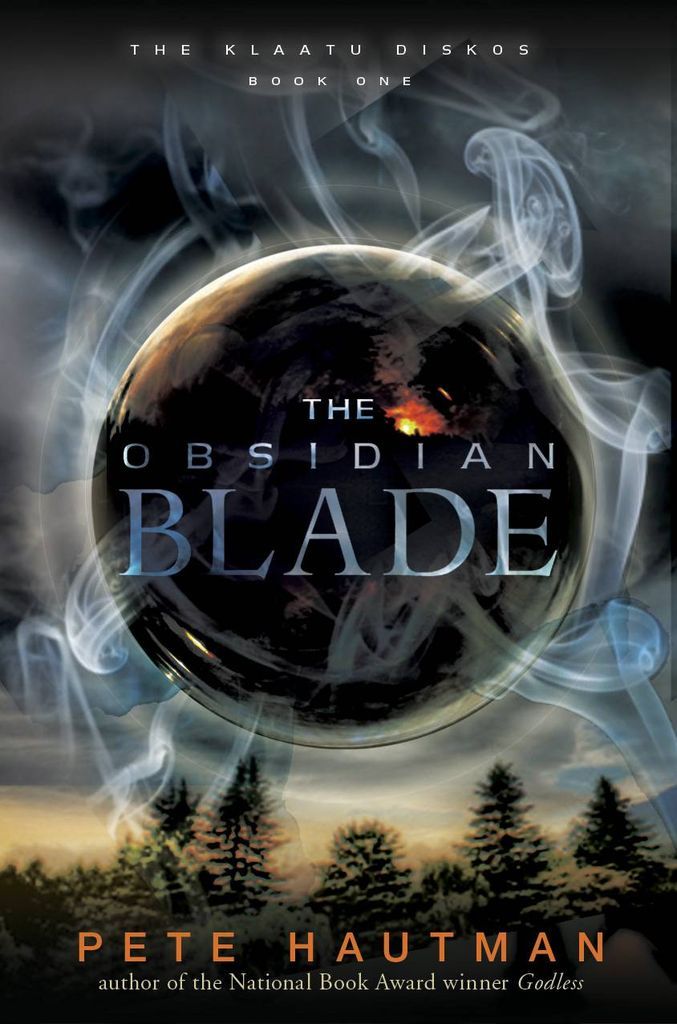

“The Obsidian Blade:” Magic Doors, Time-Traveling Maggots, and Believing

This is a guest post from Pete Hautman, whose novel The Obsidian Blade is out now from Candlewick Press. Hautman won the 2004 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature for his novel Godless. Follow him on Twitter @PeteHautman.

A recurring dream from my childhood: I discover a small, child-size door in the back of my grandmother’s bedroom closet, and it takes me to strange, sometimes wonderful, sometimes frightening places: a room filled with lost toys, an abandoned topiary garden, an ancient tomb. Those dreams were—and are—as vivid and real as any part of my waking life.

My first magic door novel, Mr. Was, was based on those dreams. I’ve since learned that magic doors are common elements in dreams: you find yourself in a house, a school, or some other familiar place, and you discover a passageway that leads to forgotten spaces. In dreams, magic doors rank right up there with flying, falling, having to take a test you haven’t studied for, appearing in public naked, or having your teeth fall out.

Shortly after the publication of Mr. Was in 1996, I began work on The Obsidian Blade, the first book in the Klaatu Diskos trilogy. While not a true sequel, it is built upon the bones of Mr. Was.

I’ve always loved magic door stories, ever since reading (and being deliciously terrified by) Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. In literature, magic door stories, aka “portal fantasies,” make up their own gerrymandering subgenre that snakes through sci-fi, fantasy, horror, and literary fiction. Examples include H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia, Neil Gaiman’s Coraline, Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, and countless other books. Movies and television have also embraced the device: Doctor Who, Stargate, and Lost are all portal fantasies.

Mr. Was is both a magic door story and a time-travel story. That’s true of most time-travel stories. Even one of the earliest time-travel novels, Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, is essentially a magic door story, although the “door” in that case manifests as a blow to the head.

In The Obsidian Blade, I call the magic doors “diskos.” The science behind the diskos is…well, you wouldn’t want to base your physics dissertation on it. But the surrounding events, featuring giant time-traveling maggots, a ruling class of autistics, and cybernetic grandmothers—are purely SF, in the same way that space operas use “warp drive” or similar device to achieve faster than light travel, then proceed to tell of believable adventures on distant planets. One is asked to swallow the device with a large gulp of Suspension of Disbelief—but all subsequent events are reasonably reasonable once the reader has accepted the premise.

This is no different than what is demanded by any novel: the conceit underlying all fiction is that we agree to believe (conditionally and temporarily) something that is not true. Believe that there is a large, white, malevolent whale. Believe that Holden Caulfield is a real person. Believe that “…a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.”

Belief is as essential to writing as it is to reading. If I didn’t believe in the diskos, I couldn’t tell their story. Years ago, after my grandmother passed away, I bought her house. The first thing I did was check out all the closets, especially the one in her bedroom. I didn’t find a magic door, but the dreams returned for a time, and while I was dreaming, I believed again.