Words, Football, Nuclear War, and the Delightful Rediscovery of Don DeLillo

If you’re like me, you’ve found two ways to consistently and satisfyingly occupy a fall Sunday:

1. Exploring the vagaries of the English language, particularly in terms of its evolution in literature and daily use in society

2. Watching football

These, of course, are not as unrelated as they may at first seem. Anyone with a working knowledge of English who also watches sports on TV with the sound turned up, can derive hours of frustration* from the constant recycling of phrases that don’t really mean what they are intended to mean and the use of qualifiers such as “obviously” and “literally” for situations that are anything but. (For example, “adversity” is not necessarily “a state of hardship or affliction” or “a calamitous event;” it is facing third-and-long, down by four, with only three minutes to go.)

*Or joy. Fortunately, someone has gone to the trouble of creating a searchable sports cliché database. If you’re a sports fan who somehow also enjoys seeing the language abused, it’s worth a look—though you may not derive as many minutes of meaningless fun from it as I did.

That said, I love many of the words that certain gifted writers use when writing about sports and even the language of sports. I have, for example, been a longtime devotee of sportswriter/author Joe Posnanski, from his (relatively recent) days at the Kansas City Star onto his current stint as a senior writer at Sports Illustrated, where he recently touched on the fact that “football has an argot all its own.” And while I have never before taken book recommendations from the SI letters section, this suggestion from a Mr. Robert Kelley of Iowa City, IA, caught my attention:

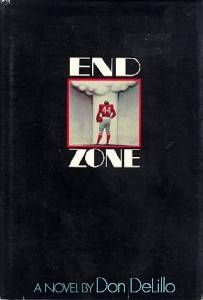

Fans of Posnanski’s column might want to consult Don DeLillo’s 1972 novel, End Zone, which dramatizes the complicated relationship between ordinary language and football jargon.

This intrigued me, because I have long considered my inability to connect with DeLillo’s prose to be a personal failing. I mean, how, when a friend first pushed a copy of it on me in college, could I possibly have not liked White Noise?*

*Here’s how: I didn’t.

But maybe I had not eased myself in. After all, as I was to find out, End Zone, DeLillo’s second novel, would come to be considered his “most accessible,” in which he tries out some of the themes that would dominate his later works, but with a—for me—more enjoyable, disturbingly comic approach.

Gary and his teammates (though not their coaches) are, of course, incredibly articulate—in dialogue and internal monologue. I found it to be a particularly refreshing read at a time when the very act of a professional football player properly making use of erudite language is considered newsworthy.

And so, nearly 40 years after End Zone was first published—and halfway through the current football season—I was pleased to have rediscovered this novel that combines two of the things I most enjoy watching in action. This is worthwhile reading for any literate sports fan or sports-minded language-enthusiast.

And obviously, I mean that literally.